Feedback is one of the best things we can do as teachers. However, it is also one of the most time-consuming, so it is crucial that feedback is highly efficient. David Didau states in his excellent Getting Feedback Right series: “Teachers’ feedback can certainly have a huge impact but it’s a mistake to believe that this impact is always positive.” The stakes are too high- if we get it wrong then teachers work increasingly long hours giving feedback which has little effect.

I see three particular parts of the process that we should refine in order to make feedback much more efficient:

- The time it takes giving feedback: We need to ensure the time spent giving feedback is as short as possible while keeping the quality high.

- Student response: We need to control the conditions under which feedback is received.

- Impact of feedback: We need to ensure that feedback is not a ‘one-hit wonder’- it isn’t quickly forgotten about.

Problem 1 and three solutions

We have to commit time to marking. Students work hard and deserve their work to be given due attention. There is a finite ‘time cost’ to marking that can’t be saved. However, it feels to me that the marking load of teachers is simply unsustainable if we don’t try to streamline the process and there are ways we we can save time in the process of writing feedback itself. Here are three ideas which I find help me to do this.

Taxonomy of errors

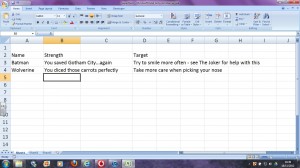

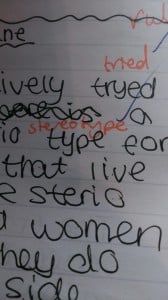

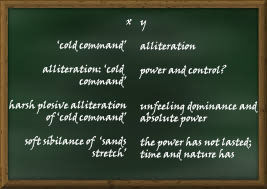

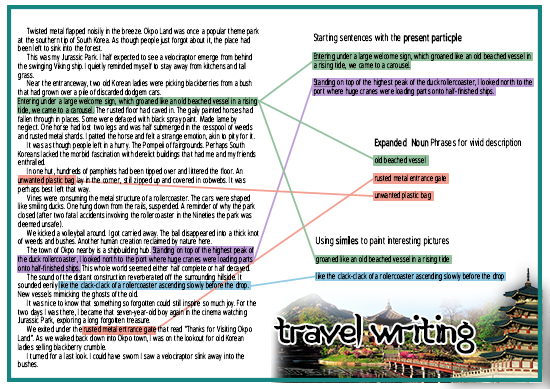

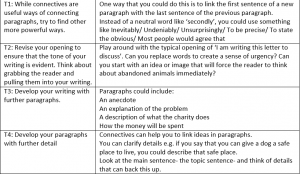

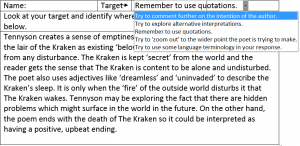

Often, when giving feedback, we tend to see the same misconceptions. If we write the same comment, plus some way for the student to improve, then we are being woefully inefficient. One approach is to create a document with all of the errors and targets. Label students’ work with T1 when a new target is generated then type this and some guidance on the sheet. When the same target comes up, write T1 again and when a new one appears write T2 etc. You end up with a target sheet such as this example of common errors in descriptive writing for use with a class. Initially, this might take longer than traditional marking but once you have created advice for, say, improving homophones, you can use it again and again.

Often, when giving feedback, we tend to see the same misconceptions. If we write the same comment, plus some way for the student to improve, then we are being woefully inefficient. One approach is to create a document with all of the errors and targets. Label students’ work with T1 when a new target is generated then type this and some guidance on the sheet. When the same target comes up, write T1 again and when a new one appears write T2 etc. You end up with a target sheet such as this example of common errors in descriptive writing for use with a class. Initially, this might take longer than traditional marking but once you have created advice for, say, improving homophones, you can use it again and again.

This approach comes from Keven Bartle, whose post here explains how you could work with a taxonomy of errors. Andy Sammons has a couple of blog posts on the subject too: DIY LEARNING: Taxonomy of Errors and Using Taxonomy of Errors for feeding forward.

Mailmerge

This is a highly efficient way of creating individual feedback for each student. It saves time on marking and you end up with an individual feedback sheet for each student.

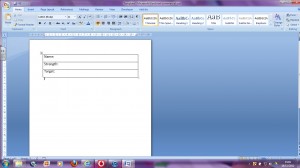

Mail merge step by step

1) Record your targets in the spreadsheet.

1) Record your targets in the spreadsheet.

2) Create a template in Word.

3) Use the mailmerge wizard>choose ‘letters’.

4) Click Next>’use current document’>Next.

5) Choose ‘Browse’ to find your spreadsheet.

6) Then click OK a lot!

7) Insert the fields you want on each target sheet.

8) Then click through ‘Next’ until you create your target sheets. You can choose ‘edit individual letters’ to then adapt them and insert tasks etc.

You can read more about using mail merge in this post.

Pre-plan feedback

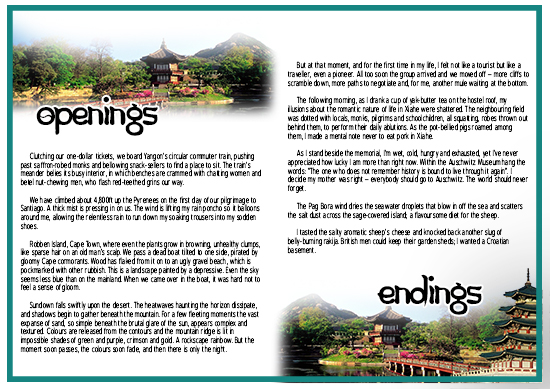

There is never a time when teachers are not busy. We do know in advance when certain assessments will take place and where we will be giving more detailed feedback. As we plan schemes of work or design a curriculum, we can also design things that will help us with our feedback. These can include some of the feedback activities mentioned above but there are other possibilities.

In the example below, I have created a model paragraph with a drop down menu. This was used during the process of essay writing. Rather than giving the feedback only at the end of the essay, this was much more formative. Bearing in mind that targets are often quite predictable in some aspects of student work, the feedback was quite simple. Obviously I needed to add some other targets and very specific feedback for others. My intervention was helpful and definitely created better essays.

In the example below, I have created a model paragraph with a drop down menu. This was used during the process of essay writing. Rather than giving the feedback only at the end of the essay, this was much more formative. Bearing in mind that targets are often quite predictable in some aspects of student work, the feedback was quite simple. Obviously I needed to add some other targets and very specific feedback for others. My intervention was helpful and definitely created better essays.

Problem 2 and three solutions

Even when we give high quality feedback, we need to remember that it needs to be received by students and sometimes we can create conditions in which students don’t really think about the feedback in the way we want them too. It is important that we do everything we can to make sure students don’t have negative responses to our feedback. I often think the analogy of how teachers feel after lesson observations is a useful way of thinking about student feedback.

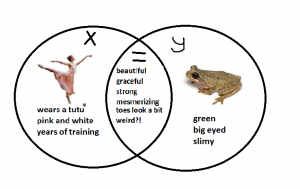

Gaps not chasms

“The purpose of feedback is to reduce the gap between current and desired states of knowing” [BUT] “…we are motivated by perceivable and closable knowledge gaps but turned off by knowledge chasms.” Hattie, Yates. It is a difficult balancing act but if we pitch our feedback wrongly then it will not have the desired effect.

Delay the sharing of grades

We want to ensure students concentrate on the feedback. Giving students grades at the same time will almost certainly ensure they concentrate on the grades. If they score highly, they ignore the feedback because they have done well. If they have not, they ignore the feedback for the opposite reason. Then they compare with the other students in the room. Best is to delay grades.

Be careful what you praise

Generic praise like ‘well done’ is meaningless unless rooted in exactly what has gone well. If we consider a Growth Mindset approach, praising effort is effective and praising talent is not. Even this is problematic as students may well work hard but make no progress so we even need to be careful about the kind of effort we praise. Praise can have all sorts of unintended consequences and we need to consider what they might be.

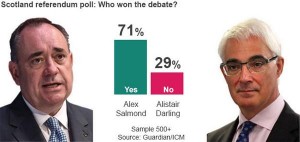

Dylan Wiliam summarises these ideas here:

(In what continues to be my most read post, I suggested a range of complex and convoluted ways that students can interact with feedback including things like ‘coded feedback’ where you write everything in code and students have to translate. Please forgive me.)

Problem 3 and three solutions

When feedback takes so long to give, we are daft if students only spend a small time on it. We need to stick with things until the student really has acted on their feedback and there is sustained improvement as a result. My old head of department used to refer to ‘pat on the head’ responses such as: “Yes miss. I will do this next time.” But they don’t- and next time they make the same mistakes. Alex Quigley has just written this cracking post on this subject which is well worth a read.

Feedback on feedback

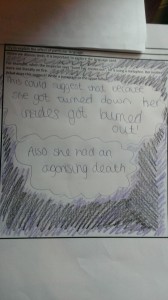

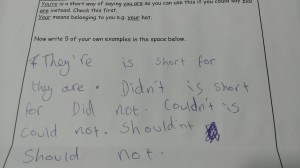

If a student has completed a task in response to feedback, check it. If any misconceptions are not cleared up, they need to be addressed. Also, you can refine the quality of your feedback by looking at responses. In this instance, the student has followed my instructions in a different way than I expected. If I didn’t check this then I may think the student can use these homophones correctly because I gave them the task. If we don’t evaluate the quality and impact of our own feedback, then the time we spend is wasted.

If a student has completed a task in response to feedback, check it. If any misconceptions are not cleared up, they need to be addressed. Also, you can refine the quality of your feedback by looking at responses. In this instance, the student has followed my instructions in a different way than I expected. If I didn’t check this then I may think the student can use these homophones correctly because I gave them the task. If we don’t evaluate the quality and impact of our own feedback, then the time we spend is wasted.

Follow on feedback

Once I have checked pupil responses to feedback, I can give them a further activity at a suitable interval to think deeply about it. Those who made no improvement get a similar target with a dramatically different task. Those who are nearly there will be able to consolidate further and those who did well will be given a ‘next steps’ activity. Not only is this ensuring that the feedback sticks, but I already know what the students need to be working on and it takes me much less time.

Feedforward feedback

Because it is crucial students master their targets, we should come back to them again and again until they stick. They should ‘feed forward’ into the next piece of work. Targets given for improvement should not be one hit wonders. If we don’t do this then what was the point of our feedback? Learning is messy and isn’t just fixed with one simple comment.

So, if we can save time writing comments, focus on the conditions under which feedback is received and stick with the feedback for longer, our feedback is going to be much more efficient. Then we can put our feet up and knock off at 3 o’clock…