While feedback is one of the most effective interventions, not all feedback is good. Many studies do show a negative effect of some feedback. An analysis by Kluger and DeNisi (1996) of 3000 research reports- and excluding a number of poorly designed reports- showed that effect sizes were ‘highly variable’ and 38% were negative. (Source: Dylan Wiliam at the Festival of Education)

Giving feedback isn’t enough. The quality of feedback matters and we spend so much time writing feedback and marking books that it is ridiculous not to ensure that the feedback is good enough. With that in mind, in this post I am casting a hyper-critical eye on a piece of feedback I gave which didn’t work in the way I wanted.

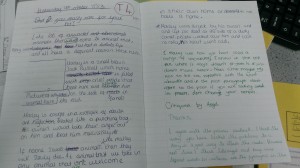

Following an essay on war poetry, a number of my year 9 students received this target: ‘Try to analyse the effect of specific language techniques’. They tended to spot a technique and use a quotation but the analysis was simple and along the lines of ‘makes the reader want to read on’ and ‘makes it more effective.’ They were given the following activity to support, based on The Woman in Black:

“…gazing first up at the house, so handsome, so utterly right for the position it occupied, a modest house and yet sure of itself, and then looking across at the country beyond. I had no sense of having been here before, but an absolute conviction that I would come here again, that the house was already mine, bound to me invisibly.”

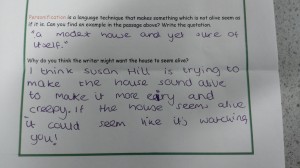

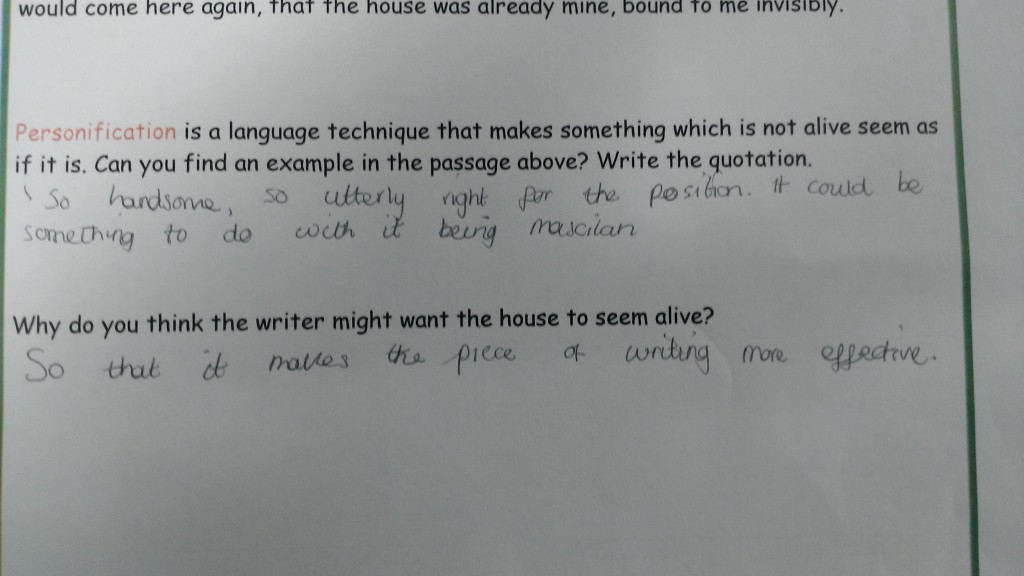

Personification is a language technique that makes something which is not alive seem as if it is. Can you find an example in the passage above? Write the quotation.

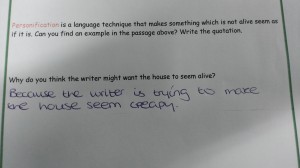

Why do you think the writer might want the house to seem alive?

Problem 1: The task doesn’t really offer any additional support

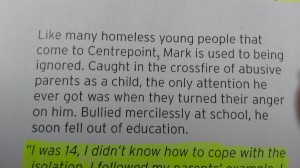

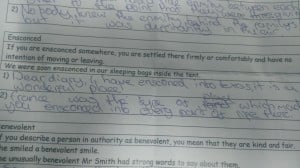

The first issue I spotted is illustrated by this example where the student has performed at the same level that they were performing at in the first place. They answered the question, but nothing in the activity, or my advice, gave them any support in answering the question better. The feedback itself might be a useful reminder for the next essay but if the student couldn’t do it before then a poorly framed task like this will not help them. The task was supposed to make students think about the effect of language. However, with no support to do it better, then nothing changed!

The first issue I spotted is illustrated by this example where the student has performed at the same level that they were performing at in the first place. They answered the question, but nothing in the activity, or my advice, gave them any support in answering the question better. The feedback itself might be a useful reminder for the next essay but if the student couldn’t do it before then a poorly framed task like this will not help them. The task was supposed to make students think about the effect of language. However, with no support to do it better, then nothing changed!

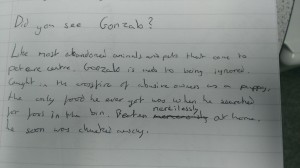

Problem 2: Poorly chosen example and poorly worded questions

The technique of personification was chosen because we were studying it in the following lesson. I think I picked the wrong example to illustrate this. Although the complexity of the text is not beyond the class, there are a number of aspects which needed explaining: handsome; modest; absolute conviction. Too much time was taken simply trying to work out what the passage was saying. This quotation is harder to analyse in the context of the whole text and I could have used an example from the start of chapter two which personified fog as evil. Students had just studied foreshadowing and pathetic fallacy so the analysis of the language would have been more straightforward and actually more precise if I had chosen that extract.

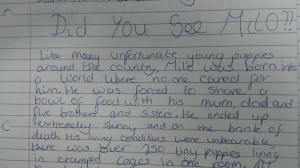

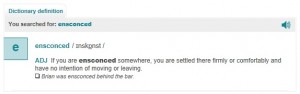

Even if the quotation had been straightforward, there is an imprecision in my design of tasks and questions. Technically, personification is a language technique that makes something which is not alive seem as if it is but this is not precise enough and certainly doesn’t get to the heart of how personification works in writing. In asking the question ‘Why do you think the writer…’, I felt that I was allowing the students scope to offer wide-ranging interpretations and I did get some thoughtful responses from students. However, the question didn’t have an explicit link with the previous one so students didn’t link the evidence they had chosen to the explanation of the effect. In the example below, I am happy that the student is exploring the effect but the response isn’t really linked to the particular quotation they have chosen.

Problem 3: The task doesn’t make them think solely about the thing I want them to think about

Doug Lemov writes in Practice Perfect,‘When teaching a technique or skill, practise the skill in isolation until the learner has mastered it.’

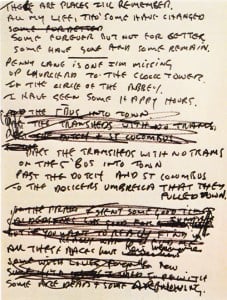

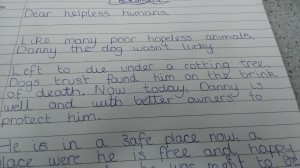

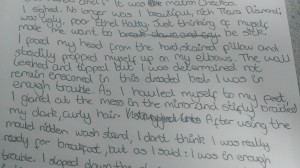

In this instance, students should have been thinking about the analysis part. I instead tried to make them learn a new piece of terminology (or at least refresh their understanding), find evidence and then analyse it. They had to do a lot of work before even getting to the key part. The final question could have been attempted without any of that part. The student below found the first part so difficult that they spent very little time on the analysis part. One student wrote nothing.

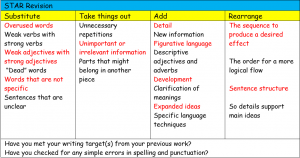

As I said earlier, I am being hyper-critical, but feedback is too important and frankly too time consuming for there to be any room for poorly designed feedback. Feedback needs to be designed so that they unavoidably think about the feedback and not other aspects. Explanations need to be crystal clear and precise to allow this to happen.

As I said earlier, I am being hyper-critical, but feedback is too important and frankly too time consuming for there to be any room for poorly designed feedback. Feedback needs to be designed so that they unavoidably think about the feedback and not other aspects. Explanations need to be crystal clear and precise to allow this to happen.