The thesis statement is the expression of the line of argument to be made in the essay. It’s an important tool in the construction of a good essay, and helps to hit some of the criteria at the upper end of the (AQA) markscheme e.g. “Critical, exploratory, conceptualised response to task and whole text.” But the statement can’t come until the idea is fully conceptualised, so how do we get students to the position where they can conceptualise the line of argument, then create the thesis statement?

The thesis statement is the expression of the line of argument to be made in the essay. It’s an important tool in the construction of a good essay, and helps to hit some of the criteria at the upper end of the (AQA) markscheme e.g. “Critical, exploratory, conceptualised response to task and whole text.” But the statement can’t come until the idea is fully conceptualised, so how do we get students to the position where they can conceptualise the line of argument, then create the thesis statement?

Lessons

A good approach when teaching an individual lesson is to frame it around a thesis of its own. So, instead of teaching a lesson on propaganda in Animal Farm, you might frame it as a thesis: corrupt leaders use propaganda and lies to gain and maintain power. This means that new information can attach itself to a clear line of argument, meaning that it can be used to help form the thesis statement later. Instead of a lesson on Ignorance and Want in A Christmas Carol, it is framed as a thesis: Ignorance and Want are used by Dickens to emphasise the consequences of mankind’s abandonment of the poor.

I think it is important that we read the book before we study it. That way, any lesson can start from the whole rather than a part. We cannot have a full conceptual understanding without knowing the whole text.

Time spent explicitly teaching and modelling planning is time well spent. It never feels like it, when we have so much content to cover, but plans that originate as mind-maps won’t have that clear argument throughout. One way is to model the construction of a thesis statement in multiple iterations. The first shows a thesis statement of sorts and how we can improve/adapt it each time.

- Napoleon is a negative character.

- Napoleon is a cruel leader.

- Napoleon is a cruel leader who manipulates the animals.

- Napoleon is a cruel leader who manipulates the animals through fear.

- Napoleon is a cruel leader who manipulates the animals through fear and propaganda.

- Orwell presents Napoleon as a cruel leader who manipulates the animals through fear and propaganda.

- Orwell uses Napoleon to criticise the way that cruel leaders keep power through fear and propaganda.

But I think the place where we can develop this most is in our students’ revision.

Revision

It is useful to design revision materials in such a way as they help students to form lines of argument about characters, themes, events in the texts that they are studying.

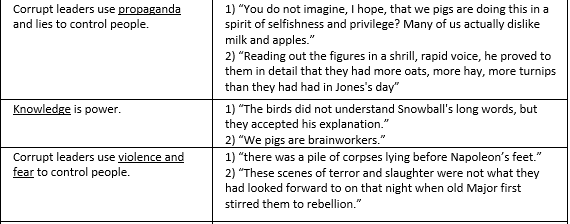

Knowledge Organisers are useful tools, but the presentation of them in hierarchical lists can be a little unhelpful when trying to organise them into more complex conceptual ideas. In our Animal Farm Knowledge Organiser, we have placed key quotations next to a line of argument in order to reinforce the idea that we don’t just memorise a quotation or a fact about a character in isolation. Instead of memorising a quotation about a character, they are memorising a quotation that supports an idea about that character.

These can make very simple Do Now activities in class. You can share the quotation and ask how they support the argument. You can have the statement and ask them to write out the corresponding quotations. You can ask them to write down any other quotations which also explore the theme or those which oppose it.

We should encourage students to make flashcards to memorise quotation. Then we have a tool for all sorts of activities to help create conceptualised responses. For example, a simple activity (for class or study) is to give a thesis statement and ask them to go through each quotation and ask the question ‘How does this quotation support the statement?’ (This is also a useful strategy for remembering the quotation itself: see this blog on memorising quotations I wrote for Bradford Research School) We can provide statements and exam questions for students, but the goal ultimately is to ensure that they can do this for themselves.

Another activity is to pick two (or more) quotations from the stack at random and ask which argument would be supported by these quotations.

To prepare for extract questions, we should pick pages and scenes that we want to explore further. If the extract is on Lady Macbeth, we ask what aspect of Lady Macbeth do we see here? Does this contrast, parallel, echo, develop from, lead to something else? Which quotations support this? It’s quite easy for students to do this themselves, and this allows them to develop an ‘extract to whole’ approach.

If studying poetry, students can easily come up with thesis statements for individual poems and memorise quotations for each poem. It’s important that their revision prepares them for the comparative focus of the exam. So, poems should generally be studied in pairs. Select any two poems and write a thesis statement comparing the poems. When memorising quotations, we should always ask, which other poem does this quotation link to and why? By studying poems in this way, it is much easier to develop that conceptualised, comparative response.

The two main problems with using quotations in essays is a) they don’t know enough so they use the only ones they know (“solitary as an oyster” anyone?) or b) they know loads but can’t choose the right ones for the essay, so the essay becomes a series of disparate points rather than a conceptualised sustained essay. These strategies help them to memorise more quotations, but also to help them pick the apposite ones to support their ideas.