Yesterday I read @SusanSEnglish’s blog: Why I love…Reflecting & realising when I’ve cognitively overloaded students! It chimed with some similar thoughts I have been having, not just about English but teaching a text like Animal Farm. As much as I find modelling writing an important teaching tool, I have come to realise recently that there are some inherent problems when modelling writing English Literature essays.

First, despite making much of the thinking explicit, we are not really showing all of the thinking. That’s because we often have a set of ideas that we are going to write about before we write a paragraph and we know the texts so well that we can choose from a range of possibilities almost subconsciously. The students only see the tip of that iceberg.

Then when students come to write, they can’t simply copy my model – my paragraph structure is unlikely to fit a different topic. And by looking at another topic, we are going to reduce the fluency of the essay writing because they are going to have to do a lot of thinking, find quotations etc.

Everything hinges on knowledge of the text, and the deep and thorough knowledge of literature texts really only comes after an extending period of study. So I have been exploring a solution – a work in progress- which is inspired by some of my thinking on combining sentences. See SecEd here for instance.

Here is a paragraph that I modelled in class, warts and all:

We also see evidence of Snowball’s leadership in the Battle of the Cowshed. Despite the fact that the pigs have already started to distance themselves from the physical labour of the farm, Orwell presents Snowball as a fearless leader who throws himself into action. There is an emphasis on movement, as Snowball “dashed” and moved “quickly.” Furthermore, the repetition of the word “launched” reinforces this idea of rapid movement and it is a leader who ‘launches’ an attack. There are consequences for Snowball, as “the blood was still dripping” after the battle, but he is remorseless in stating that: “The only good human being is a dead one”. Orwell shows the power of violence here, but also the power of knowledge, as Snowball “studied an old book of Julius Caesar’s campaigns”. While this battle at first is a representation of the Russian Civil War, and Snowball’s leadership mirroring that of Lenin and Trotsky, it hints at the ways that the pigs will later exploit the other animals through their superior knowledge and use of violence, long after Snowball is gone.

There is so much underlying knowledge to this paragraph and my essay is a result of me juggling all of these ideas (or propositions):

- Repetition of “launched”

- “launched”, “quickly”, “dashed” all show movement

- The pigs normally don’t get involved in physical work

- Snowball is a fearless leader

- “The only good human being is a dead one”

- “the blood was still dripping”

- This battle represents the Red army’s victory over the White army in the Russian Civil War

- The power of Snowball’s leadership is evident

- Orwell shows the power of violence

- “studied an old book of Julius Caesar’s campaigns” – power of knowledge

- Knowledge and violence are tools used to exploit the animals later on

With this in mind, teaching how to build a good paragraph is actually teaching how to combine all of these ideas. My first attempt in getting students to build an answer using propositions started with me giving them another list:

- Boxer is capable of violence: “terrifying spectacle”/ “rearing”/ “striking”

- “His very first blow took a stable-lad from Foxwood on the skull and stretched him lifeless in the mud.”

- He is remorseful: ‘I have no wish to take life, not even human life,’ repeated Boxer, and his eyes were full of tears.

- Simile: “like a stallion”

- A stallion is a horse used for breeding. It is strong and powerful.

- Boxer is a work horse.

- Boxer represents the proletariat, which means that he symbolises the ordinary worker.

- Orwell shows how it is often the ordinary people who fight wars and who suffer.

- Orwell ultimately shows this with Boxer’s sad demise.

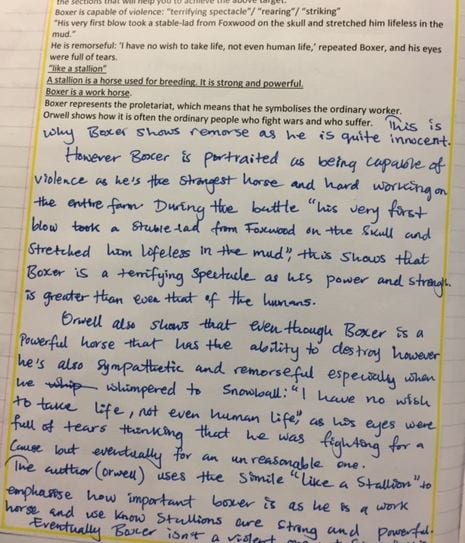

I felt that this process would be quite successful. However, when I looked at a few examples, I could see that students had just dealt with these propositions in order. Going in at the start with many many propositions doesn’t help students to combine ideas effectively and is not representative of the writing process.

I felt that this process would be quite successful. However, when I looked at a few examples, I could see that students had just dealt with these propositions in order. Going in at the start with many many propositions doesn’t help students to combine ideas effectively and is not representative of the writing process.

The next step then was to combine these ideas together in smaller chunks:

- Simile: “like a stallion”

- A stallion is a horse used for breeding. It is strong and powerful.

- Boxer is a work horse.

- A dramatic transformation occurs.

In my modelling, I showed how these could be combined in different ways:

When Orwell uses the simile “like a stallion” to describe Boxer, we understand how Boxer is transformed in battle from the downtrodden work horse to something far superior.

It is interesting that Orwell shows a transformation in Boxer, from the reliable work horse to something far superior. The simile “like a stallion” demonstrates how dramatic this transformation is.

I won’t jettison the writing of whole paragraphs, but I certainly will be spending more time combining ideas like this. Sentence combining for writing is a regular staple of my classroom practice, but I hope that it becomes just as common for essays too.