I welcome the reports into teacher workload and I hope that school leaders read them and implement some of their recommendations. Here are my initial thoughts on the data, planning and marking reports:

For leaders, not teachers

These reports are ultimately for the benefit for teachers, but if you have no control over your school’s policy, you will find little practical inspiration from them. The problem with workload is that it is often closely linked with your school and your leadership team. In the marking report, it is stated: “If the hours spent do not have the commensurate impact on pupil progress: stop it.” Yet if you are the NQT who does this, you are possibly going to fall foul of the next book scrutiny. You can see that there are only two recommendations specific to teachers in the marking report, two in the data one and two again in the planning, which reinforces the idea that the audience is not actually classroom teachers.

However, it’s not necessarily a bad thing that the advice is aimed at leaders and institutions. Teachers are very rarely the sources of their own workload problems. They are at the mercy of the “policy” and the “initiative”. I appreciate that the marking report states:

Evaluate the time implications of any whole school marking assessment policy for all teachers to ensure that the school policy does not make unreasonable demands on any particular members of staff.

The Data report:

Take measures to understand the cumulative impact on workload of new initiatives and guidance before rolling them out and make proportionate and pragmatic demands.

When I filled in the survey myself, this was something that I wrote about. Lots of things are good things to do, but they take up time. It is up to leaders to make these choices. There is a vagueness in what is meant by “unreasonable demands” and I am sure different people will have their own ideas about what this means, but it’s so important that we ask this question.

Broad advice

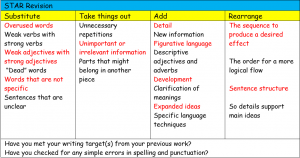

I do feel that this sense of imprecision runs through all of the reports. For example, the marking report recommends ITT students develop “a repertoire of assessment methods” and teachers use “a range of assessment techniques” without being precise about what these look like. If you are a teacher struggling with the marking workload, being told to use a range of techniques isn’t helpful when those techniques are not clear.

There are definitely principles that everyone should get behind and there are not many parts of the report that I disagree with. For example, the suggestions of making marking “meaningful, manageable and motivating” seems sensible. These terms are then defined in more detail, so can serve as a very useful starting point for any marking policy.

Once something is said to be good practice, it can take on a life of its own, so I appreciate why these reports need to be careful. It is much easier to say what shouldn’t be done than to say precisely what should (except posters…). There are some case studies on the blog and there will hopefully be more, although this one recommends different coloured pens and writing VF for verbal feedback in books so perhaps we should be careful with these too.

I really like the line in the planning report that “there should be greater flexibility to accommodate different subject demands and needs, as well as the specific demands of primary phases.” It is important to acknowledge that there is much variation in subjects and phases, not just with planning but other demands too. Should an English teacher teach the same load as a maths teacher? Should a teacher who has predominantly KS5 have the same teaching load as one who teaches mainly KS3?

Workload issues in the planning report

The planning report has good intentions but some of its recommendations seem to lead to more time:

School leaders should place great value on collaborative curriculum planning which is where teacher professionalism and creativity can be exercised.

I agree that shared planning can be beneficial, but where does the time for this come from? It has to come from somewhere. Similarly, the demand to create “a fully resourced, collaboratively produced, scheme of work” as a default is a noble one but I can assure you that this is a time-consuming process and someone has to do this. I’m not arguing that this shouldn’t be done, just that to create a really good scheme of work that can be used by anyone takes time.

I have always struggled with the fact that there are not some free central resources that all teachers can access. Ones that they can adapt for their context, change and share back. TES can be useful, but there is a massive quality control issue- try to look for a lesson on similes (smiles/ similies) and you’ll see . Also, the idea of teachers selling their resources runs counter to a profession where we should be interested in helping each other. This happens on Twitter of course but I feel that the DfE should appoint teachers to make schemes, perhaps as a summer project, or recruit experienced, recently retired teachers to do it. Even just creating a quality controlled shared site would be a start.

On textbooks, I agree with the recommendations that we should use them but it is not a “mistrust of textbooks” but a lack of good enough ones that I am more concerned with. Textbooks are a huge investment when curriculum content changes so often, so the DfE should look at ways to make this commercially viable.

All in all, I think the reports make sensible recommendations that will impact positively on workload. We just need more concrete examples of what should be done.