I have not always seen eye to eye with mini whiteboards. I hated handing them out, storing them, pens running out, pens going missing, not having enough, doodles, scribbles, drawings of inappropriate things, drawings of me, inappropriate drawings of me. In the past I would trot them out every so often before inevitably dismissing them as just too much of a hassle. Yet now I use mini whiteboards in every lesson and I can’t imagine teaching without them. Perhaps these are not the most fashionable tools in the education world, but here are the reasons why I find them indispensable.

Whiteboards are a way of getting immediate feedback about student understanding, with an effective sequence always starting with a well-designed task or question. Rather than just waiting as students write, this time can be used to seek the most useful responses. Do most students get it or not? Where are the great examples that can be used as models? Where are the examples of common errors that students can learn from? Which students are making the same errors?

Depending in what our checking tells us, there are many options:

- Stop the task and reteach something immediately.

- Give a simple piece of corrective advice to address a common problem e.g. ‘remember to mention the writer’.

- Choose a range of responses (usually three) for students to compare.

- Pick one example that is ‘nearly there’ and ask the class to improve it.

- Sequence the responses shared so that they become increasingly more sophisticated.

- Find answers with a common thread and ask students to connect them (really useful for language analysis).

- Find three errors and ask students to connect them.

- Teach the students who don’t understand in a small group. See in-class interventions.

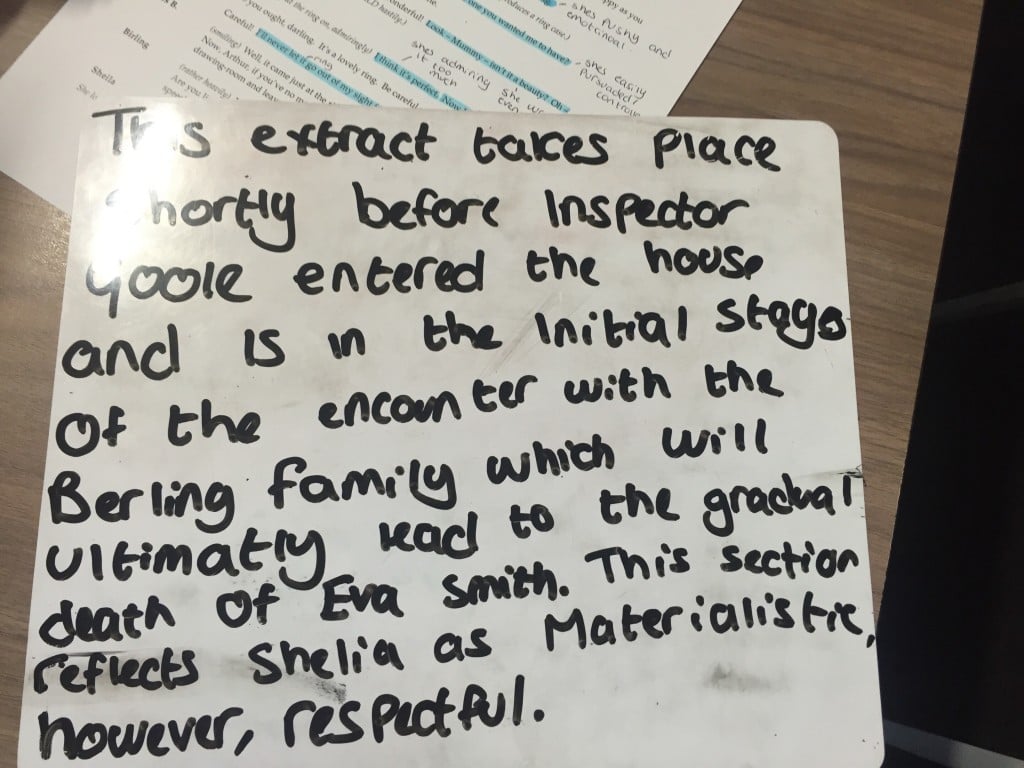

If the first board I checked was this one, I would be thinking about spelling, particularly character names. Is this student the only one getting these wrong? I know that in this lesson I shared a model paragraph on the board and the phrase ‘ultimately lead to’ has been lifted from that and used incorrectly, so I need to know if others have made the same error. I could choose this board to look at the spelling of ‘ultimately’. We could use it as a fairly decent first attempt at an opening paragraph and ask students to rework it to make it better. I could seek out another contrasting set of adjectives used to describe Sheila and ask students to compare. Or I might not use this board at all-there are plenty of others to choose from! The main thing is, I don’t want to leave it to a randomly selected student response and hope it tells me something. By getting every student to write a response to a clear and unambiguous question (not ‘hands up if you don’t understand’), I can be reasonably sure of the class picture and do something about it.

If the first board I checked was this one, I would be thinking about spelling, particularly character names. Is this student the only one getting these wrong? I know that in this lesson I shared a model paragraph on the board and the phrase ‘ultimately lead to’ has been lifted from that and used incorrectly, so I need to know if others have made the same error. I could choose this board to look at the spelling of ‘ultimately’. We could use it as a fairly decent first attempt at an opening paragraph and ask students to rework it to make it better. I could seek out another contrasting set of adjectives used to describe Sheila and ask students to compare. Or I might not use this board at all-there are plenty of others to choose from! The main thing is, I don’t want to leave it to a randomly selected student response and hope it tells me something. By getting every student to write a response to a clear and unambiguous question (not ‘hands up if you don’t understand’), I can be reasonably sure of the class picture and do something about it.

There are other benefits of using whiteboards too. One of the issues that we have, as I am sure many schools do, is the use of unnecessary fillers in spoken responses. Part of the reason for this is, I feel, is students’ lack of confidence in what they are saying. Or that they don’t know what they are going to say before they start saying it. The few seconds it takes to write a couple of ideas down on a whiteboard can help to eliminate both of these. Add in grammar issues, not answering in sentences and the ubiquitous ‘innit’, and we have a number of elements that a quickly prepared written response can help to eliminate.

I want my students to develop excellent habits of editing, proofreading and redrafting. Whiteboards help me to create a culture where this is expected. It starts with making sure the first thing they write is high quality, and there’s an increased accountability when students write on whiteboards. When they know it will be held up and discussed, there is an incentive for it to be their best work. It’s easy to edit work quickly on a whiteboard and far less messy. With a constant focus on the quality of these short responses, students start to self edit, even as they are reading out their answers. They can spot the errors in other students’ answers and then fix their own. It’s easy for the teacher to correct the spelling of the word ‘beginning’ on a board and then instruct others in the class to fix it if they made that mistake. It’s great for adding commas or colons in the right place. Even as students write in their exercise books, they can make notes on whiteboards.

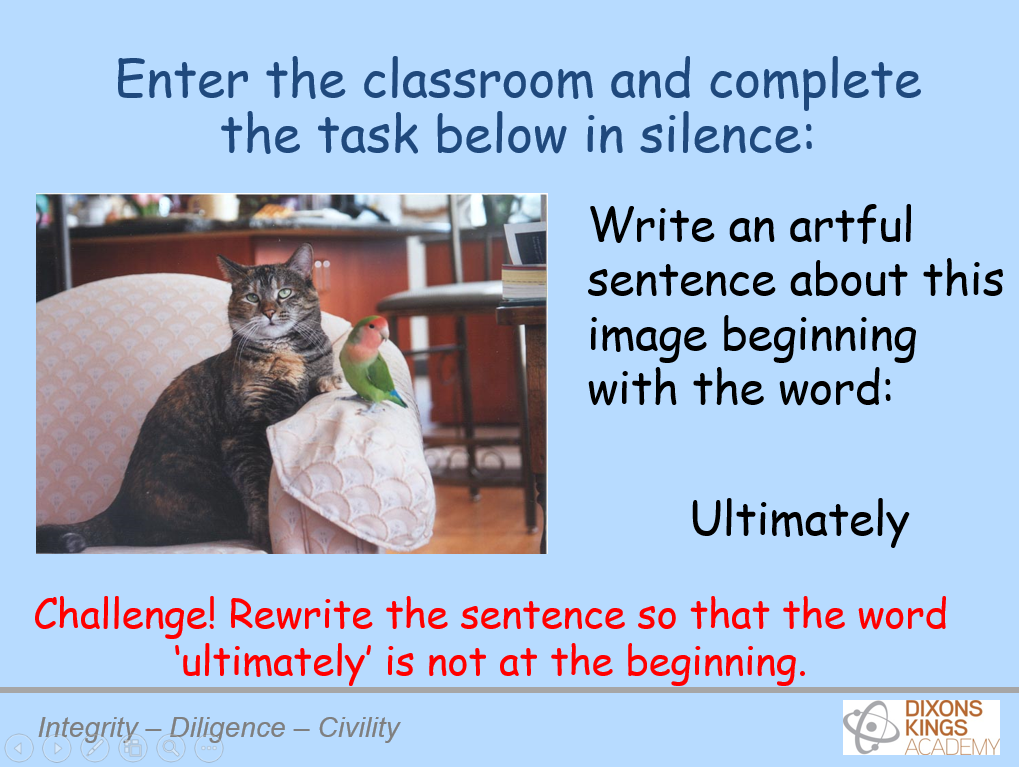

Every lesson at our school starts with a Do Now which is completed on the whiteboards. It means that lessons start in a calm and prompt manner and it is efficient when we don’t have to wait for books to be handed out. The ability to immediately write something down on whiteboards can also help to eliminate the ridiculous amount of time it takes for some students to write the title and date.

Every lesson at our school starts with a Do Now which is completed on the whiteboards. It means that lessons start in a calm and prompt manner and it is efficient when we don’t have to wait for books to be handed out. The ability to immediately write something down on whiteboards can also help to eliminate the ridiculous amount of time it takes for some students to write the title and date.

Some argue that teachers might only do work on whiteboards in order to avoid marking books. Well, of course! And there’s nothing wrong with that. The fact is, I’m not going to mark everything students write in their book and I can’t mark it if it is only in their head. If it is written on a whiteboard, I am giving immediate feedback and in a fraction of the time it takes to mark books- in many ways it is more beneficial than marking books.

But what about the problems that I listed before? Surely these won’t go away. Much of what we try and do at Dixons Kings is to make it easy for teachers to teach and students to learn, so behaviour systems and classroom routines are crucial to ensure students don’t often exhibit those off-task behaviours. As for the equipment issues, every classroom has a set of whiteboards on desks and students must carry a pen with them as part of their essential equipment. Without these systems, I wouldn’t use whiteboards, especially as I don’t have my own classroom.

We designed a mini whiteboard routine which is used by all teachers in the school. When we want students to hold up their boards, we say, “3-2-1… show me.” They hold boards up with two hands then we say “track student x” and that student reads their answer out. We come back to these routines in our practice sessions to ensure they are consistent. There are some who might argue that these routines reduce creativity or lead to ‘robotic’ teaching. Yet they have allowed me to be the most creative I have ever been as a teacher and I would welcome anyone to come and visit to see just how much this routine and some of the others free teachers up to actually teach. Without these whole school approaches, you can still design a whiteboard routine that works for you. Consider in advance how equipment is stored and handed out and expectations during the sequence.

So, have a rummage in your stock cupboard, find the discarded whiteboards (I guarantee there will be some) and start using them.