Every lesson has at least one moment where the teacher has to decide whether to move on. ‘Have they got it?’ we ask. The next step seems clear: stay with something when students don’t ‘get it’ and move on when they do. But is it ever as simple as all of the students understanding or not understanding something? Not in my experience- it will usually be proportions of the class who get it. So re-teaching or moving on aren’t the only possibilities. It is much more complicated than that.

The moment we teach something, we may have one, two or fifteen students who don’t get it. We need to know who they are and do something about it. In this, the second part of my TLT15 presentation, I will explain how we can use in-class interventions to close gaps even as they appear.

The right questions > intentional checking > in-class intervention

If we are going to intervene effectively, the information we get needs to be valid and it needs to be from everyone. It can’t just be the odd student, like the one who shouts out “I don’t get it”, leading the teacher to stop the whole class for an explanation that they don’t all need. Questioning a selection of students will only tell about those students and asking students if they get it will only tell us about perception. The only methods that can give us a true picture require every student to participate and give an answer that is unambiguous. Hinge questions are particularly useful for effective diagnosis- read Harry Fletcher-Wood’s excellent series of posts on this topic. Mini whiteboards are the easiest low-tech way to gather accurate student information across a whole class and there are of course some high-tech ways too. We can also make decisions about individual understanding from simply reading students’ work.

We need to be intentional in our data gathering, ready to intervene in the most appropriate way. When students are completing tasks, or when they are answering questions on mini-whiteboards, teachers should be looking for specific things that they will address. When we teach the lesson and design the questions, we know what the common misconceptions are and need to look for them-it shouldn’t only be responding to whatever comes up.

At this point, teachers should be deciding what happens next: the in-class intervention. If 3 or 4 students are struggling with something, then they can be retaught while the rest of the class works. If a small number ‘get it’ then perhaps they can work on an additional task while the whole class is retaught. You might have a case where one group of students has struggled with one aspect while another has struggled with something else- set them all off on a task and then teach each half in turn. There are any number of possibilities.

I watched a Maths lesson recently where the teacher put a question on the board and gave students 3 minutes to complete it on whiteboards. Instead of simply waiting for students to hold them up, the teacher walked round and looked at every single student. When it came to holding boards up, struggling students had already been identified, as had those who understood, common misconceptions were gathered, two different methods spotted. A student was asked to share an example of the misconception, which allowed the teacher to explain the correct method again. After this, a group of three were taken to the front for another go while the rest of the class completed more questions. It was a sequence designed and implemented to ensure that all students understood.

Create the culture for it

I actually don’t think the concept or the implementation of in-class interventions like this are difficult. I think the hardest part is creating a school and classroom culture to allow these to take place effectively.

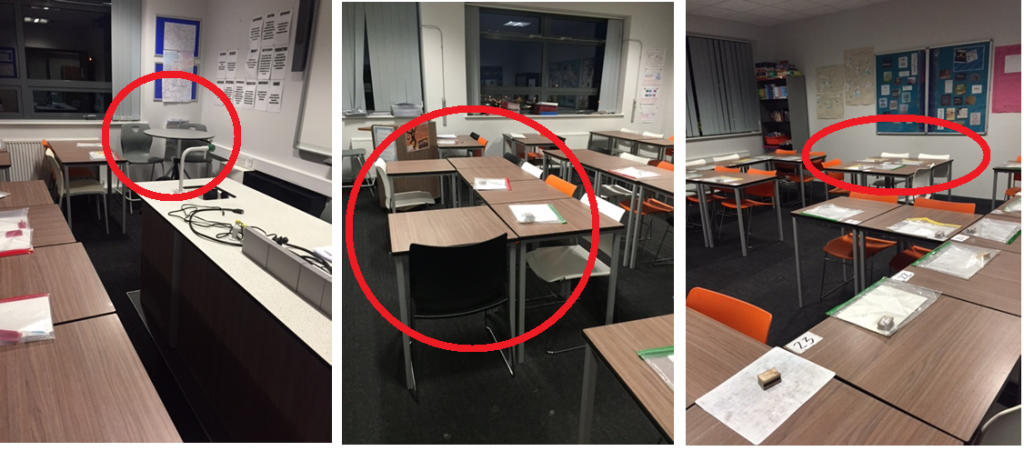

If teachers are going to teach small groups while the rest of the class work, they need to have classrooms designed to facilitate this. These images of classrooms from my school show areas designed specifically for intervention. In the first image, the table in the corner is used and its position ensures that the teacher can scan the rest of the room as she intervenes. The horseshoe shape of the second image is a space that can accommodate several students and is right at the front to allow the teacher to monitor the rest of the class.

Teachers cannot establish the right culture of diagnosis and immediate intervention if the rest of the class start misbehaving when they intervene. That is why it is crucial that school systems take the hard work of managing behaviour away from teachers. If teachers have to deal with many incidences of poor behaviour, interventions won’t work, and if they are chasing up detentions and making endless calls home then they are not planning. Clear expectations of behaviour, consistently demonstrated by teachers and supported by senior leaders with centralised detentions, means that this small group teaching is much easier to manage. I have written about our consistent approach to behaviour at Dixons Kings Academy here.

Teachers cannot establish the right culture of diagnosis and immediate intervention if the rest of the class start misbehaving when they intervene. That is why it is crucial that school systems take the hard work of managing behaviour away from teachers. If teachers have to deal with many incidences of poor behaviour, interventions won’t work, and if they are chasing up detentions and making endless calls home then they are not planning. Clear expectations of behaviour, consistently demonstrated by teachers and supported by senior leaders with centralised detentions, means that this small group teaching is much easier to manage. I have written about our consistent approach to behaviour at Dixons Kings Academy here.

We don’t even get to the intervention stage without useful information, so teachers need to see mini whiteboards as routine and not a nuisance. (How many mini whiteboards sit unloved in stock cupboards?) At DKA, we have whiteboard language and routines designed to make using them hassle-free. Students must carry a whiteboard pen around with them as part of their essential equipment (with a detention on the day if they don’t), once again making it as straightforward as possible to use whiteboards.

I am conscious that an approach which requires planning for different outcomes to a question may in fact lead to excessive planning. While it is true that planning may be made more complex, it doesn’t necessarily require creating resources as intervention can just be teaching. Anyway, any resources created, to use Joe Kirby’s word, are renewable. It’s just feedback- and it will take much less time than marking a set of books. And if you get it right with the initial teaching of concepts then you probably don’t have to waste as much time or energy later coming back and dealing with the problems.