One of the best things about my job is that I get to see lots of other people teaching, and this week I noticed a common thread in lessons that allowed me to reflect on my questioning, and then, in a roundabout way, on my teaching of writing.

In particular, I saw No Opt Out, a technique taken from Teach Like a Champion, used expertly in several lessons. This is the idea that when a student says “I don’t know”, you stay with them until they get it, or give various cues to support, or ask another student before returning to them. As Lemov writes: “In the end, there’s far less incentive to refuse to try if doing so doesn’t save you any work, so No Opt Out’s attribute of causing students to answer a question they’ve attempted to avoid is a key lever.” It’s something that we practised in CPD last year and it was great to see it being used in lessons.

Yet there are some very real problems that can occur when this is used. Momentum can be lost when you stick with a student, especially when the question might just be a quick check that forms part of an explanation. It can mean that others in the class switch off, which is not great, especially when the strategy is designed to eliminate this kind of thing. I felt a little of this ‘switching off’ in one of my own lessons this week.

These are the pitfalls of No Opt Out. But the strategy exists for the long term gains rather than just for addressing the moment where students don’t get it. This happens over time by building a culture in the classroom where “I don’t know” is rewarded with “Great. I’m going to help you so you will know.” It becomes easier to think when the question is asked than to avoid it. Showing that you will probe is a way of ensuring that you don’t have to probe in the long run, but you have to keep doing it until everyone works it out. This can then mean that the best exponents of No Opt Out rarely have to use it! Or, at the very least, they know that “I don’t know” actually means that and not “I haven’t thought about it.”

So why did this lead me to think about writing? Well, by coincidence I have been teaching redrafting, which is another method which we can make obsolete after a while. When we explicitly teach it well, we can get to a point where we rarely have to do redrafting. Once students have the habits effective in redrafting, they can become proficient in revising work, editing things as they write. I have been using Kelly Gallagher’s STAR Revision mnemonic (which I think is one of the few useful ones in English) to model this. You can read more about this in Revision Before Redrafting.

It takes work to build these habits, but once students know how to do it, they can do it in their head, they can do it mid sentence, they can reorder sentences in paragraphs as they write. You barely have to teach it again.

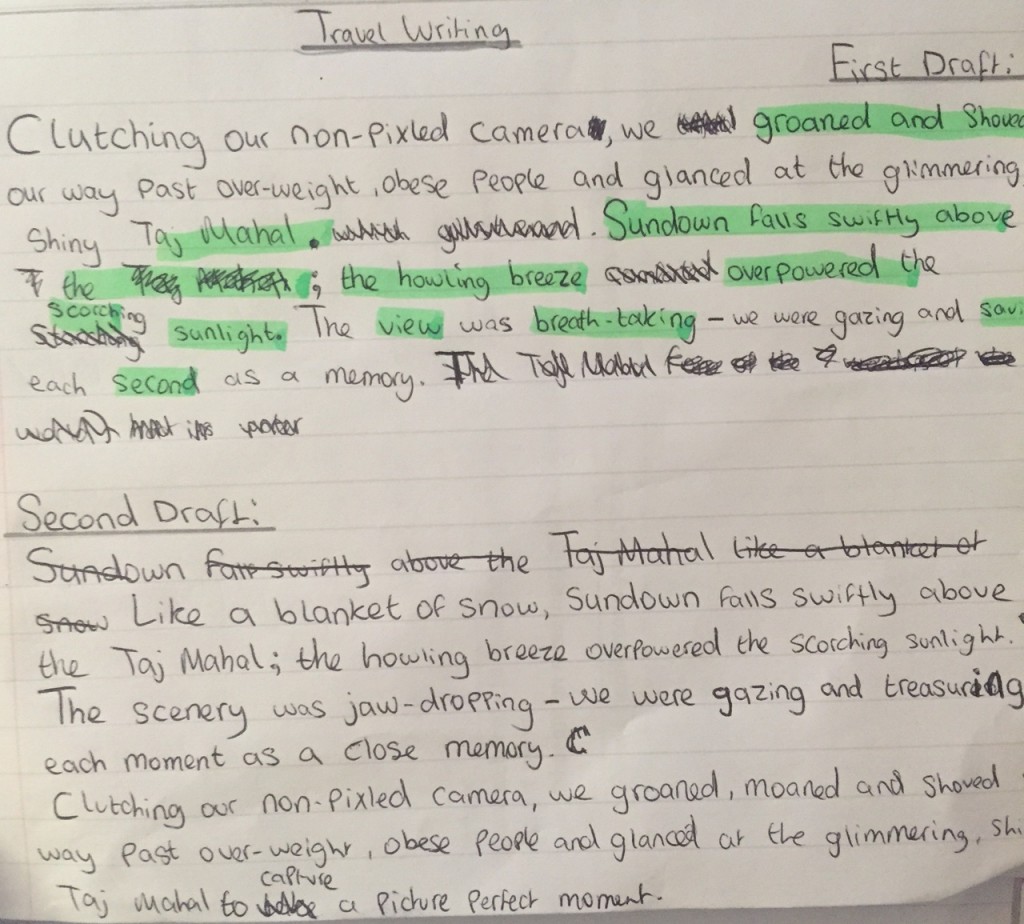

Here are some examples of how this works, taken from one of my classes this week. In the first example, the task was to redraft the opening. You can see lots of changes, with perhaps the most interesting one that it now starts with a simile.

Here are some examples of how this works, taken from one of my classes this week. In the first example, the task was to redraft the opening. You can see lots of changes, with perhaps the most interesting one that it now starts with a simile.

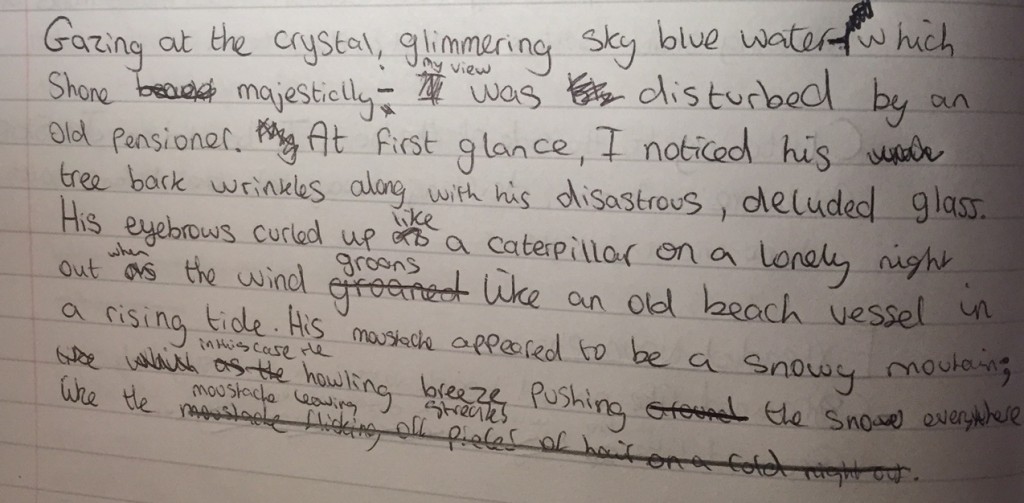

In the next example, a different student is now consciously revising as they write. This was the very next lesson after the explicit teaching of redrafting. You can see them change their mind halfway through ‘beautifully’ and constantly revise their writing. Is it perfect? Not yet. But it is almost a second draft without writing the first.

In the next example, a different student is now consciously revising as they write. This was the very next lesson after the explicit teaching of redrafting. You can see them change their mind halfway through ‘beautifully’ and constantly revise their writing. Is it perfect? Not yet. But it is almost a second draft without writing the first.

![]() The final example has just one word changed. The man holds a photograph on his heart rather than his stomach. I love that.

The final example has just one word changed. The man holds a photograph on his heart rather than his stomach. I love that.

Looking at the messy examples above reminds me that another keep-doing-it-so-you-don’t-have-to-do-it strategy is being fussy about presentation! Whether it is thinking, revising or using a ruler, persevering at the start means that you will rarely have to do it again.