In an article for the New York Times, Robert Sapolsky writes the following:

Symbols, metaphors, analogies, parables, synecdoche, figures of speech: we understand them. We understand that a captain wants more than just hands when he orders all of them on deck. We understand that Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” isn’t really about a cockroach. If we are of a certain theological ilk, we see bread and wine intertwined with body and blood. We grasp that the right piece of cloth can represent a nation and its values, and that setting fire to such a flag is a highly charged act. We can learn that a certain combination of sounds put together by Tchaikovsky represents Napoleon getting his butt kicked just outside Moscow. And that the name “Napoleon,” in this case, represents thousands and thousands of soldiers dying cold and hungry, far from home.

This idea is fundamental to English teaching. In the texts that we study, things represent other things. Sometimes we are ushered as readers towards them quite clearly and other times they are puzzles for us to solve or flights of fancy for us to follow. James Geary, in his fascinating book I is an Other, explains metaphor in a simple equation: x=y. This equation is simple shorthand but it captures this idea in our subject that something we can focus on (x) sheds light on or represents another aspect (y). I would consider this to be a threshold concept: a ‘big idea’ that when understood will have a powerful impact on how students succeed in English. Once they ‘get it’, they are unlikely to go back. However, it can be difficult to spot when this hidden code is at work.

Sometimes metaphors are pretty obvious. One such example is from Norman MacCaig’s lovely poem Frogs:

[frogs] make stylish triangles/ with their ballet dancer’s*/ legs.

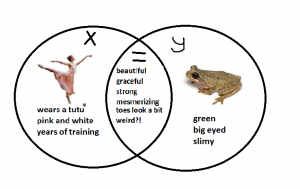

The image is simple and works. We appreciate the physical resemblance. x (frogs’ legs) = y (ballet dancers’ legs). Elsewhere in the poem, frogs are ‘parachutists’, ‘Italian tenors’, ‘Buddha’. I love this poem in its simplicity- frogs are a bit like all of these things. However, even this has much more complexity if we explore it.

While a student certainly won’t be wrong if they comment on the physical similarities, they need to consider more: what are the things we can say about ballet dancers’ legs that we can also say about frogs’ legs? But it is more than this: what are the things we can say about ballet dancers that we can also say about frogs? Or, even: what are the things we can say about ballet dancers that Norman MacCaig wants us to think about nature? If students can grasp these layers of meaning then they will move beyond a straightforward interpretation of the phrase and the poem. Because then the comparison isn’t about frogs’ legs being like ballet dancers’ legs, it’s really about nature being beautiful and complex and graceful and strong. It’s about the fact that MacCaig can see in a creature and in a moment the beauty of the world.

While a student certainly won’t be wrong if they comment on the physical similarities, they need to consider more: what are the things we can say about ballet dancers’ legs that we can also say about frogs’ legs? But it is more than this: what are the things we can say about ballet dancers that we can also say about frogs? Or, even: what are the things we can say about ballet dancers that Norman MacCaig wants us to think about nature? If students can grasp these layers of meaning then they will move beyond a straightforward interpretation of the phrase and the poem. Because then the comparison isn’t about frogs’ legs being like ballet dancers’ legs, it’s really about nature being beautiful and complex and graceful and strong. It’s about the fact that MacCaig can see in a creature and in a moment the beauty of the world.

The MacCaig example is a poet with his cards on the table and yet there are still so many layers. Robert Frost describes these layers of meaning as ‘feats of association’.

All thought is a feat of association: having what’s in front of you bring up something in your mind that you almost didn’t know you knew. Putting this and that together. That click.

The ‘feats of association’ are often subtle; they don’t hit us over the head and announce themselves. The ‘click’ isn’t always instantaneous. As John Fuller says in Who is Ozymandias, “The suspicion is generally and often rightly held that poetry is ‘about’ something other than its ostensible subject, and that there is a reason for its concealment.” Speaking of Ozymandias, my year 10 class have been studying it this week and the biggest challenge has been grasping the concept that the poem is a metaphor and that it isn’t really about a statue, it is about what the statue represents. If we don’t approach the poem as this kind of metaphorical puzzle then it really is just about a statue. There are also so many aspects of the poem which might seem arbitrary (like the rhyme) or inconsequential (like the traveller) if we don’t think in terms of allusion and metaphor.

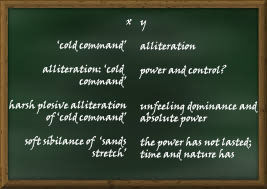

So here’s where x=y comes in handy again. If students can balance the equation then they can solve it and unlock the poem. If they mention a technique for the x part then the equation needs to be balanced with the y of effect. If they comment on a theme in the poem (x) then they need to balance that with how that theme can be related to the wider world (y). This way of thinking makes them consider how anything they spot might have an intended effect rather than simply listing techniques. It also helps them to be disciplined when addressing the question, in our case about power and control. In the example in the image, we look at the effect of the alliteration. That could be explored even further, with all of those final ideas becoming a new x and wider points about power becoming a new y.

So here’s where x=y comes in handy again. If students can balance the equation then they can solve it and unlock the poem. If they mention a technique for the x part then the equation needs to be balanced with the y of effect. If they comment on a theme in the poem (x) then they need to balance that with how that theme can be related to the wider world (y). This way of thinking makes them consider how anything they spot might have an intended effect rather than simply listing techniques. It also helps them to be disciplined when addressing the question, in our case about power and control. In the example in the image, we look at the effect of the alliteration. That could be explored even further, with all of those final ideas becoming a new x and wider points about power becoming a new y.

Of course, poetry is the place where we expect this trickery, but it is everywhere. x is the dagger before Macbeth, x is Squealer in Animal Farm (x is everything in Animal Farm!), x is the shopping mall in Dawn of the Dead.

It’s a concept which can improve writing too. How often do students just write when what we want is for them to consciously craft writing? Even students who can analyse writing well don’t necessarily reverse engineer great writing themselves. By thinking about the y of their writing, then the x parts become rather straightforward. For example, if they want a particular tone in their writing then the vocabulary choices need to balance that equation.

This isn’t a neat mathematical equation and I would be loathe to reduce everything to this. Nonetheless, I think it’s an interesting way to approach a fundamental aspect of English.

*This apostrophe has bothered me.

Further reading:

Alex Quigley’s blog on Threshold Concepts is well worth a read.

I is an Other is a fascinating look at the role metaphor plays in our lives. His TED Talk on the same topic is here.

I is an Other is a fascinating look at the role metaphor plays in our lives. His TED Talk on the same topic is here.

Who is Ozymandias? is a book about the puzzles in poetry.

Who is Ozymandias? is a book about the puzzles in poetry.