On Thursday I took a walk around the school during a lesson changeover. Students were walking out of lessons quietly and calmly, teachers were greeting their new classes as they arrived, and within 3 minutes work was taking place. Every lesson was different, but there was a consistency that meant that it was easy for students to learn. This wasn’t left to chance; it was the result of two hours of dedicated practice of classroom routines seven days earlier.

Our routines are so important, but when systems and routines are the sole preserve of the classroom teacher, we get inconsistency. And inconsistency is unfair. It’s especially unfair on the students, because they don’t know what to expect. Behaviour that is acceptable in one lesson suddenly merits a sanction in another lesson. It’s unfair on the experienced teacher who works tirelessly on developing their own classroom routines that are not followed elsewhere. It’s unfair on the new teacher, who needs to create classroom routines on top of the many many other things they must do. It’s unfair on the Teach First participant or the cover supervisor, who haven’t got the benefit of established routines.

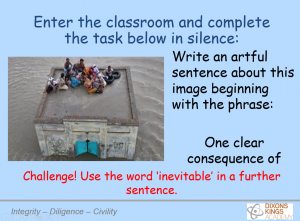

So a school approach to classroom routines helps to ensure that consistency. At Dixons Kings Academy, we have tried to unpick the moments in lessons that could benefit from shared expectations and routines, from the habits for individual, paired and group work to the shared routines for mini whiteboard use. Yes, some elements are prescriptive – scripting of how we bring a class to silence for example- but these routines are designed to make it easier for teachers to teach the way that works best.

If we say a routine or expectation is important, then it can’t just be sent out in an email or relayed as a ‘policy’. It needs to be exemplified and practised, which is why we dedicated time to practising our entry and exit routines on our first day back. In addition to building consistency, practice shows us where we are going wrong (or where we might go wrong) and need to improve, but also helps reinforce what we are doing well, making us more confident and comfortable in the classroom.

We practised how teachers line students up, how they greet them, the way they bring them into the classroom, and complete the Do Now activity. We then practised how to end lessons (standing behind chairs in silence, teacher scanning the room to ensure that it is tidy, an orderly dismissal).

It’s a simple practice method. We share a model of what is expected, staff practise once through in groups of about six, receive feedback then repeat. Everyone practises, and everyone feeds back at least once. While the models that we practise are carefully considered, they are open to feedback, and practising will often identify the flaws, creating better models in future.

The group that I practised with had a couple of new members of staff. The practice was useful for them in internalising everything they had been told about- and as you might expect on the first day back- they had been told a lot. Think of that first lesson when students are sizing up their new teacher and the teacher starts the lesson just like the experienced senior leader. Immediately, the new teacher carries just a little more authority. For me, as someone who seems to forget completely how to teach by September, it was great to warm up. I won’t have my own classroom this year, so my entry and exit routines have become even more important. The practice session allowed me to consider things that I may have otherwise left to chance. For example, where do you stand at the end of the lesson? How do you move around the room? How do you dismiss classes from your classroom? How does this change in a completely different room? I don’t think that these are trivial questions at all.

There are more things to practise of course, and we won’t spend every session on the absolute basics, although we should never become complacent. With a relatively small amount of time spent on embedding simple whole school routines, we free teachers up to concentrate on the complex art of teaching.

Next week: how we practise in subjects.