If you have read Teach Like a Champion 2.0, you’ll be familiar with ‘The Art of the Sentence’.

The technique is described as follows:

Ask students to synthesize a complex idea in a single, well-crafted sentence. The discipline of having to make one sentence do all the work pushes students to use new syntactical forms.

Sentences are the simplest mentor texts and students with a command of effective sentence-building tend to produce the best writing. At my school, Dixons Kings Academy, we’ve been starting every lesson with The Art of the Sentence. It’s a simple strategy with a massive impact.

Improving thinking

A well-constructed sentence is about more than just literacy. The best sentences actually improve the quality of thinking. As Doug Lemov writes, “…helping students learn how to write increasingly complex, subtle, and nuanced sentences is teaching them to develop increasingly complex, subtle, and nuanced thoughts.”

Here is an example from a list of analytical sentences shared by Andy Tharby:

________is motivated not only by… but also by…

This construction enables-or forces- students to think in a specific way about the text. As students are presented with more and more of these sentence constructions, they will reach for just the right one when they want to think precisely about a concept.

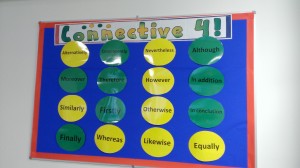

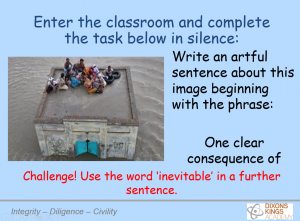

We asked staff to reflect on the habits of thinking we needed to develop in our students and then designed sentences to promote this. For example, in many subjects there is a need to consider and then express cause and effect. Which sentences might help students to develop this habit of thinking?

We asked staff to reflect on the habits of thinking we needed to develop in our students and then designed sentences to promote this. For example, in many subjects there is a need to consider and then express cause and effect. Which sentences might help students to develop this habit of thinking?

As a result of_______________, ______________________.

One inevitable consequence of___________________

____________________________ is a direct result of

Precision of expression is crucial not just at the sentence level, but at the word level. Most words are learnt from context, not through the teaching of them, and a single encounter with a word will be unlikely to ensure full and rich knowledge. But repeated exposure to a range of carefully chosen words is an approach worth taking. (See Choosing which words to teach)

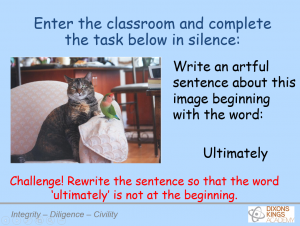

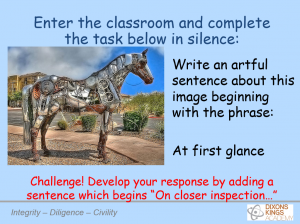

Every lesson starts with an artful sentence. While the sequence can be extended and sentences studied- as I do repeatedly- this can also be completed quickly at the start and the simple routine makes lesson starts more purposeful. I use mini whiteboards, some teachers use computers, some books and some just ask students to think of their response. The immediate habits of thinking and working set the tone for the rest of the lesson: no minute is wasted in the pursuit of learning. Teachers then transition into the teaching of the subject.

Our Director of Literacy took on the mammoth task of creating slides, trawling the internet for interesting and unusual images to use, and designing just the right sentences.

Initially, there were small issues that needed addressing. Some students were using the sentences without the precise meaning. For example, one student in my class wrote, “Ultimately, there is a cat and a bird.” This follows the instructions of the task, but with no real understanding of why we should use that word. Also, with the wrong image /sentence combination, sentences don’t really work either. “On the surface” only works if there is something deeper that is not on the surface. The first time that students encounter a word such as “inevitable”, it probably has to be explained. The second time might require another explanation but students soon get it.

In one of my recent lessons, students were writing a paragraph comparing Helena from a Midsummer Night’s Dream with a typical Elizabethan woman and I saw this: “Helena differs from a typical Elizabethan woman in a number of ways respects.” This topic sentence construction had been used on a number of slides. Then, in another lesson, a student wrote: “Ultimately, Romeo is a tragic hero and is fated to die.” I hear the sentences in class discussion and see them in writing with increasing frequency.

Next steps

So far, we have used the same sentences across the school, but we will shift to making them more subject specific, allowing students to develop the vocabulary and precision of thought in a particular subject discipline. We will also increase the complexity of some of the sentences now that students are grasping the concept. At present, we have been constructing sentences based on images but next will be graphs, extracts from literature, historical sources.

Further reading:

Doug Lemov on The Art of the Sentence

David Didau on The Art of Beautifully Crafted Sentences

Chris Curtis’ Death to Sentence Stems! Long Live the Sentence Structures!

Andy Tharby’s Sentence Escalator