Stabilisers helped me to learn how to ride a bike. But until I took the stabilisers off, I couldn’t say that I was able to ride a bike. I have been considering the role of classroom ‘stabilisers’ and how in some cases we might be keeping them on for too long. These stabilisers- or cues- take different forms, from displays to thesauruses and the way that we inflect our voice when we say something like, ‘Is that a simile or a metaphor?’ With too much of these, students become very good at recognising, but not so good at recalling.

We can think of students’ knowledge as appearing on a continuum as follows:

subconscious understanding > familiarity > recognition > recall with a cue > recall.

(paraphrased from Memory: A Very Short Introduction)

Our job is to shift students’ knowledge along that continuum. If they cannot get to the ‘recall’ part, then do they know it at all? Much of the time we keep students at the ‘cues’ stage, where they can perform pretty well in a lesson but without actually being able to do the thing that we want them to do or remember the thing we want them to remember in the long term.

With too many cues, students are just using ‘maintenance rehearsal’ i.e. just learning something enough to get through a lesson or a task. With this, there is a danger that nothing stays in long term memory as the deep thinking required for this to happen is not present. Our ultimate job as teachers is to encode the knowledge, ensure it is stored, then put students in a position where they can retrieve the knowledge without needing our cues.

Interestingly, the act of retrieval itself helps to make things stick and allows students to create their own cues: “Each act of retrieval alters the diagnostic value of retrieval cues and improves one’s ability to retrieve knowledge again in the future.” (Karpicke, 2012)

Bearing all this in mind, I have been considering some of my current practice and implications for change:

Display

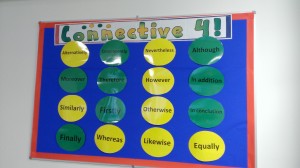

This is one of my displays, showing a range of connectives. It is helpful to refer to but now I have a concern that the display doesn’t help students in the way I want it to. Students are never asked to recall the connectives if they are in plain sight. Recently, I have been removing connectives and asking students to recall the missing one. I must confess that I cannot make up my mind whether this display is a help or a hindrance. Advice is welcome.

This is one of my displays, showing a range of connectives. It is helpful to refer to but now I have a concern that the display doesn’t help students in the way I want it to. Students are never asked to recall the connectives if they are in plain sight. Recently, I have been removing connectives and asking students to recall the missing one. I must confess that I cannot make up my mind whether this display is a help or a hindrance. Advice is welcome.

Feedback

When we provide feedback we often provide prompts or directions for next steps. We could design even better feedback which requires a follow up activity some time afterwards where students are asked to recall. For example, we might give students an exercise on homophones which explains the rules and asks students to identify (i.e. recognise) which homophones have been used incorrectly in a range of sentences. One week later, we might ask them to write their own sentences or explain the rules of homophones themselves- asking them to recall. This is not something I currently do. I ask students to reflect on whether they meet their target but not by asking them to recall. I’m going to experiment with this form of follow up retrieval homework over the next term.

Vocabulary

For students to be able to use a range of vocabulary expertly, we need to shift it from that zone of recognition- they understand it when they read it- to it being part of their regularly used spoken and written vocabulary. Spending too much time searching for the right word in a thesaurus will not have that effect. Displays with key words will be helpful to a point but with no guarantee students will recall them in the future. We know that students need multiple exposures to words in different contexts before they will be readily recalled and used. See this post for some further thoughts on vocabulary instruction.

‘Mats’

I think literacy mats or similar can play a part in the classroom. I can see that they might be beneficial for students writing at length in other subjects but I have mixed feelings about them in English. Much like the connectives on the display above, by giving students a mat with, for example, all the punctuation they need to use for a certain level, are we in fact hindering them over the long term? The mats need to be taken away at some point and I would argue that they should be taken away completely. The cognitive load produced by a learning mat can be overwhelming too. Students spend so much time looking at a number of things that they have to include that they lose sight of what they have to do.

I will be using ‘mentor mats’ this half term. These are still a form of cue but consist of mentor texts for study with some elements highlighted for closer inspection. The cognitive load is reduced. There are still cues but these are the isolated areas for study in the unit, rather than a checklist of things to include. Because these cues are in the form of model sentences, they require more thinking than ‘You should include x’. Here is the text from a mentor mat to get the idea.

Curriculum Design

We should design curricula with the opportunities for students to encounter the material they need over and over again, removing the cues and increasing the amount to be recalled. This means that we might teach a concept for the first time and provide all of the supports and then revisit it later without them. For example, in a year 7 scheme of work I have just designed, students will write about The Kraken. Tennyson uses personification in the poem and I want students to be able to comment on it. Therefore, several weeks before, at the start of the scheme, students are taught about personification, encounter the technique later in a short story, revisit it in another poem, The Second Coming, and then read The Kraken. At this point, we hope students can recall the technique unprompted.

This is not a post arguing that cues and scaffolds and supports are not necessary- they play an important role in the learning process. Sometimes it is only repetition of certain cues that force things into long term memory. For example, the C, B, A, mnemonic was important for me to recall the pedals when learning to drive. This cue was never ‘removed’, it just became unnecessary after a point.

If we wish to isolate a skill for practice, we may also provide support on other aspects. For example, when I am looking at sentence structure, I may well offer model sentences and example sentence starts. When I want students who struggle with extended writing to comment on a text, I will often provide scaffolds for support. However, this is always with an end in mind, leading students towards the place where they will be able to do this without the prompts.

Further reading:

David Didau: Deliberately difficult – why it’s better to make learning harder – essential reading on ‘desirable difficulties’.

David Fawcett: Can I be that little better at…using cognitive science/psychology/neurology to plan learning – a must read exploration of key principles of cognitive science.

Stephen Cavadino: Why calculators should be banned (and for balance- a counter argument)