Every poem is an island. To get to a poem requires sailing out from the mainland of routine language. Some poems are close to shore, others much further away; on every island it is possible to feel remote and at home. A poem is defined by the rugged shore of its right-hand margin, cutting it off from prose.

Robert Crawford

When I think back to my first encounters with poetry as a boy, I realise that I often understood poems, yet I simply didn’t get poetry. Later as a teacher, I have spent an awful lot of time working on how I will teach individual poems, but not nearly enough time on how to teach poetry. If I continue the metaphor above, I have focused on the island but not the archipelago, or the…er…ferry journey (this is why I’m not a poet). With the prompt of this month’s #blogsyncenglish, I thought it was time that I did. So, how do we get to a point where a poem is no longer something remote, something that only exists in isolation?

Sequencing- building a bridge

No poet, no artist of any art, has his complete meaning alone. His significance, his appreciation is the appreciation of his relation to the dead poets and artists. You cannot value him alone; you must set him, for contrast and comparison, among the dead.

T.S. Eliot

An example of a poem that I have ‘taught’ recently is ‘Tissue’ by Imtiaz Dharker. When teaching this, there was just so much I had to tell students and with that came a number of shortcuts. A poet was reduced to “Born in Pakistan. Brought up in Glasgow. Conflicted.” Teaching the poem in isolation led to these kind of generalisations. (Of course, it wasn’t completely in isolation, because I was teaching it as part of the conflict cluster. AQA can dictate that it is in the conflict cluster but what it has in common with The Charge of the Light Brigade I am not sure.) I felt that my teaching of the poem was fine; my class knew the right things to write about and understood the main idea. But it was just a poem on its own.

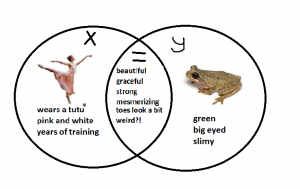

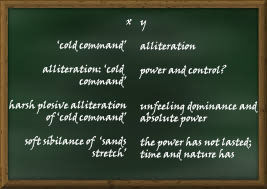

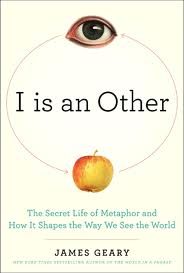

I don’t have time to teach any other poems by Dharker, but wouldn’t it have been much better if we’d studied more of her poems earlier and appreciated a body of work that this was only a small part of? Could we study other poets dealing with similar themes? Would there be a special combination of poems we could study in sequence that would mean that we arrive at ‘Tissue’ ready for it? If a poem is a specially constructed puzzle, can we give them the clues beforehand, and if we can, what are they? For starters, a more comprehensive grasp of metaphor would have helped my students with this particular poem.

Whether our ultimate goal is to prepare students for literature exams or whether we just want them to develop an appreciation, perhaps a love for poetry, we need to think quite carefully about the sequencing of poems.

The sequencing of learning about poetry should start early. It need not be dictated just by the poems selected by an exam board, especially when these might change, but it does need to be selected consciously. And not just a poetry unit each year where students study a bunch of interesting poems, often favourites of the teacher, or perhaps collected together under a common theme. Then they get to year 10 and rattle through poems in the anthology before we finally make sure that we give enough tricks and mnemonics to cope on the unseen poetry questions.

I’m honestly not sure about what the ‘correct’ sequencing of poetry should be. Should we, for example, start in year 7 with Shakespeare’s sonnets and move towards contemporary poets in later years? Should we start with simple poems? Should we start with poems of a certain structure? Should we rattle off one of each kind of poem in an introduction to poetry unit? These are important questions to ask and ones which a new curriculum gives us a chance to answer.

Relevance- spotting landmarks

Poetry is common. The stuff of it is common, even commonplace. Poetry comes from what we as human beings have in common. It puts us in living touch with our shared realities.

David Constantine

This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless-about to be birthed, but already felt.

Audre Lorde

Because poetry is often shrouded in ‘high style’, it can be difficult for students to have this illumination, particularly when a poem is usually brief. Students can seem to ‘get’ other texts more readily because they spend time finding what they have in common with characters and how the themes affect them. It is never hard to empathise with characters, but isn’t it strange that we can find more in common with a citizen of District 12 who kills a bunch of fellow children than we can with a poet pondering their own mortality?

I’m not an advocate of making everything relevant in the classroom, but in many ways poetry is so valuable because it is universal and relevant. If we can somehow tap into this and help our students to identify the connections, they will navigate the islands of poetry fearlessly. I know that a child may not quite need the reminder that we all do of the fleeting nature of time, of the inevitably of death etc; starting a lesson with “we’re all going to die…which is why this is a GREAT poem!” might be ill-advised. Yet because much of our poetry deals in universal truths- even if these truths can themselves change- we can expose students to great examples of poems that do connect.

There are obviously lots of ways to navigate individual poems, but with a little thought we can at least ensure that they arrive on the island with a map.