Over the last couple of years, sentences have played a prominent role in my classroom. Students know what good sentences look like, can often discuss the mechanics of them, but lately I have encountered a couple of problems.

One is that students decide the type of sentence, then fit the content to it. For example, they will decide to use an embedded clause, then begin to write it, throwing in whatever detail springs to mind. It’s the same way of thinking that leads to random rhetorical questions clunkily arriving in persuasive writing and is perhaps an inevitable consequence of informing students that they must use certain techniques in their writing. I want them instead to have the idea in mind, and the effect, then construct the right sentence to express it, choosing the structures that work best in that instance.

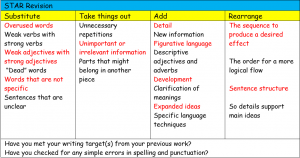

Another problem is that students commit to sentences and once a sentence is written, it is very rarely changed. On redrafts, individual words are often replaced, sentences are added to paragraphs, but the basic sentences don’t change all that much.

So, to help address these issues, I have been trying to model explicitly all of the decisions that writers make when they construct great sentences. This helps the first problem because students look at different options before committing, and with these additional options they should be more confident in rearranging sentences, addressing the second problem.

To illustrate how I am doing this, let’s look at a sentence from Il Duro by D.H. Lawrence, an 80p Penguin Classic:

He suddenly began to speak, leaning forward, hot and feverish and yellow, upon the iron rail of the balcony.

We can’t see all of the writing decisions that Lawrence made. He had to choose the ideas, the words themselves and then the syntax. To begin to explore the third of these in particular, we can break the sentence up into its basic ideas, or propositions, of which I see eight:

- He began to speak.

- He spoke suddenly.

- He leant forward.

- He leant on the balcony.

- The balcony had an iron rail.

- He was hot.

- He was feverish.

- He was yellow.

By my reckoning, there are 40,320 different ways to organise these eight propositions. I like to ask students to put these together, without changing the main ideas or the words (except for verb endings). This means that they have to make some of the choices that the writer had to make. Crucially, they start with the ideas to be expressed and not an arbitrary sentence construction. It is the order and relationship of these propositions that will lead to subtle differences in meaning.

With this sentence, I know in advance the kinds of things that will likely be up for discussion. Why is “He suddenly began to speak” the main clause? Why not “He leant forward”? What happens when we change “leant” to “leaning”? Why “hot and feverish and yellow” and not “yellow and feverish and hot”? And so on. And we can ask questions of the students about their choices too. Then we can compare: students with each other, then students with the writer.

In these discussions, we look at the ways ideas can be combined. Through coordination, subordination, through causal relationships, right branches, left branches, colons, commas, appositives, prepositions and present participles.

Here are the propositions from another sentence in the book:

- Her head was tied in a kerchief.

- The kerchief was red.

- Pieces of hair stuck out over her ears.

- The hair was short.

- The hair looked like dirty snow.

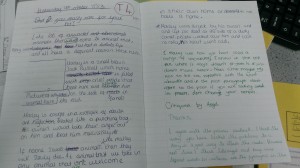

At #TMBRAD, we had a go at writing sentences from this:

@GoldfishBowlMM “Tied in a red kerchief, the short pieces of her hair stuck out like dirty snow over her ears. #tmbrad

— leah ellerbruch (@LEllerbruch) July 11, 2015

Audience participation #TMBrad: Her hair, short, dirty like snow, stuck out over her ears underneath her red kerchief @GoldfishBowlMM

— Jennifer Webb (@FunkyPedagogy) July 11, 2015

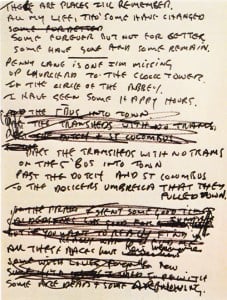

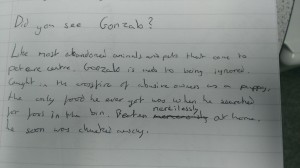

Trying to figure out the sentence! We were close! Another brilliant idea to steal! @GoldfishBowlMM #TMbrad pic.twitter.com/5uzZ2kp4rU

— Laura Hirst (@MissLHirst) July 11, 2015

The actual sentence: “Her head was tied in a dark-red kerchief, but pieces of hair, like dirty snow, quite short, stuck out over her ears.”

This isn’t a particularly ground-breaking approach- it is pretty much just sentence combining after all- but it’s new for me, and it’s improving my students’ writing. As Jeff Anderson writes, in Revision Decisions:

But the point of combining is not simply to put two sentences together (one sentence…and…another sentence) to make a long sentence. The point of sentence combining is for young writers to see relationships among ideas and to discover more effective ways to show these relationships […] Sentence combining is about playing with ideas and shaping them into effective syntactical patterns that make sense for individual writing situations.

Further reading:

Revision Decisions is another wonderfully practical book from Jeff Anderson, and inspired the ideas above.

Revision Decisions is another wonderfully practical book from Jeff Anderson, and inspired the ideas above.

Building Great Sentences by Brooks Landon covers similar ideas, and there is an audio course from The Great Courses on the same subject by the same writer.