When I realised my year 11s were not revising English as much as I wanted this year, I first went to my usual strategies: 1) long rants about why they should study and 2) giving them more revision materials – as if the solution to them not studying the things I had already given them would be to give them even more things!

But after a little more discussion and some pupil interviews, it was clear just how much they were struggling with the demands of many challenging GCSEs – and every teacher expected them to revise heavily for their subject. These were pupils for whom securing a 4 in English would be an excellent achievement and for many of them the fact isn’t that they were refusing to revise, but that they didn’t know where to start. And even when they started, some didn’t really know the most effective ways to proceed. Here are some strategies I took to try and address things.

Making the first step easy

The Behavioural Insights Team have developed the EAST framework (Easy; Attractive; Social; Timely) as a way of changing behaviour. They say that the “small, seemingly irrelevant details that make a task more challenging or effortful (what we call ‘friction costs’) can make the difference between doing something and putting it off – sometimes indefinitely.”

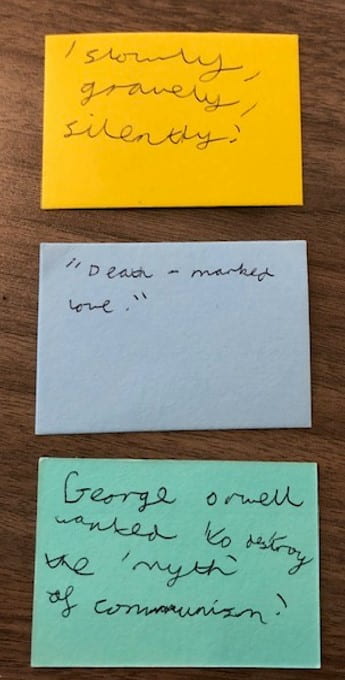

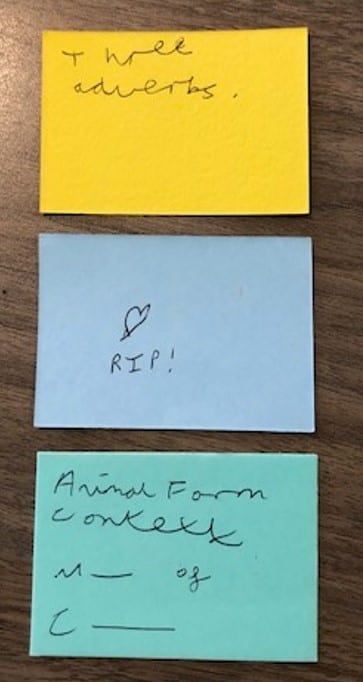

With two English GCSEs, and 4 papers, 3 texts, 15 poems, terminology, strategy, etc to consider, you can see why some pupils struggle to get going. For those who don’t know where to start, we have to make the first step easy. And this means creating a single tangible step which can then lead logically to a next step. For example, ‘memorise quotations’ could become: Identify 5 quotations for Banquo > Write 5 quotations on flashcards > Write a cue on the other side > Use the Leitner system to memorise. The abstract becomes concrete.

But even this can fall down on the first step because pupils might not have flashcards. They might not know where to start identifying quotations. They need to know what a cue is. Any friction can lead to giving up. When setting up these initial practices with my class, I provided the quotations and also provided flashcards. (A6 size are optimal – they are easier to carry in a pocket and there is no temptation to fill the cards with lots of text.)

But even this can fall down on the first step because pupils might not have flashcards. They might not know where to start identifying quotations. They need to know what a cue is. Any friction can lead to giving up. When setting up these initial practices with my class, I provided the quotations and also provided flashcards. (A6 size are optimal – they are easier to carry in a pocket and there is no temptation to fill the cards with lots of text.)

I have often heard some pupils say that you can’t really revise for English Language but there are definitely many ways that they can, but without a tangible first step they won’t, so this was a particular focus for me. Any urge to just hand out tons of sheets of paper was met with the question: what is their first step?

Model desirable difficulty

Even if a first step is taken, it’s really hard to sustain revision. And let’s not pretend that we are all that different from pupils. I have just checked twitter, eaten some peanuts, chosen a different album to listen to in the space of writing this paragraph. And this whole blog post has been sitting unfinished for weeks, so pupils don’t have the monopoly on procrastination and giving up.

But we do need to make it easier for pupils not to give up. When things get tricky, pupils will always default to the easiest option, so they will reread notes to feel that they are fluent, they will revise subjects they like or are successful in, they will avoid the tricky topics. All because they are hard and it is not enjoyable. One way is to help them understand that it’s not too much of a problem if revision is difficult. In fact, it’s quite helpful.

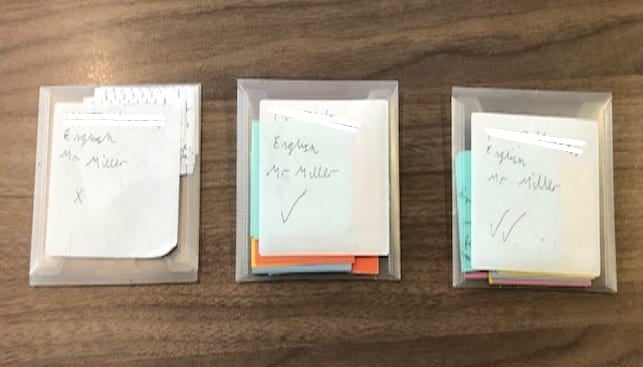

The Leitner system is an effective way of building in retrieval practice, but it can be a challenge when trying to memorise a lot of new material, because there will be quite a lot of failure. (If you are not sure what I am talking about here, watch this short video).

The Leitner system is an effective way of building in retrieval practice, but it can be a challenge when trying to memorise a lot of new material, because there will be quite a lot of failure. (If you are not sure what I am talking about here, watch this short video).

When introducing any strategy like this, I would recommend spending a lesson using the strategy, pausing regularly to discuss what is happening, reflecting with pupils before, during and after the process. With my class, this was important because it gave them a reference point for when they were struggling on their own. Because we started with a small number of quotations/ flashcards, there was an element of success too.

The pupils who always seem to find revision and study easy are those who can self-regulate. Zimmerman (2002) sets out these features of a self-regulated learner: Setting short and long term goals; using appropriate strategies to attain these goals; monitoring their performance; restructuring their physical and social context; managing time efficiently; self-evaluating; attributing causation to results; adapting future methods. None of these come easily, so modelling each stage can help to stop pupils giving up.

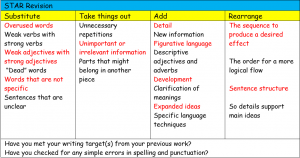

When sharing or devising revision strategies with pupils, try to identify those that have elements of this built in. For example, the Leitner system has the monitoring part and also allows pupils to adapt their methods. Techniques like exam wrappers can also account for lots of stages in this cycle.

Build revision in

By the time pupils get to what Sir Alex Ferguson would call ‘squeaky bum time’, they have filled several exercise books and have a locker or a desk drawer overflowing with revision materials and handouts. Mine are no exception. I have changed quite a lot about teaching GCSE from the start for future classes, which I have written about here, such as using exercise books as revision guides, so I wanted to build in similar principles for anything that I handed out. Anything given as a resource or a task in class would be designed to become a revision resource.

An example is this handout for a lesson on George Orwell. I would previously have given a handout with all the information and maybe some reflection or consolidation activities linking to the text. I still did those, but I wanted this useful knowledge to last and not be forgotten. So an adaptation of the Cornell note-taking system was created. The summary helps with the immediate consolidation, but the design of cues should facilitate retrieval practice later on. It turned a simple sheet of text into a revision resource. Joe Kirby has written about Renewable Resources as an important tool to reduce teacher workload and students using these resources as part of later revision certainly reduces workload.

An example is this handout for a lesson on George Orwell. I would previously have given a handout with all the information and maybe some reflection or consolidation activities linking to the text. I still did those, but I wanted this useful knowledge to last and not be forgotten. So an adaptation of the Cornell note-taking system was created. The summary helps with the immediate consolidation, but the design of cues should facilitate retrieval practice later on. It turned a simple sheet of text into a revision resource. Joe Kirby has written about Renewable Resources as an important tool to reduce teacher workload and students using these resources as part of later revision certainly reduces workload.

The goal in all of this was not for me to do the work, but for me to get things going. I jump-started the car but they drove it.*

*I like this last line but please don’t think about this metaphor too much as it probably isn’t as profound as I think it is.