Last week I read this article from John Blake: “The solution to the workload crisis? Stop teachers designing their own lessons.” I found myself agreeing with the sentiments, so I read the full report: Completing the Revolution: Delivering on the promise of the 2014 National Curriculum. I thought it was sensible and attempting to address some very real problems in education – I would recommend reading it.

I understand the issues that some people have with what Blake terms “oven ready resources” and the fear of robotic automatons reading from a script, but my concerns at present are the unhealthy hours that teachers work. Something has to give. My sense is that far from being a restriction, having some well crafted, quality-assured resources and curriculum programmes will help to sharpen up the way that we teach material and improve our work-life balance. The report calls this the Final Foot:

As well as lowering their workload, such “oven ready” resources will also help teachers focus their professional expertise on “the final foot” between them and the children they teach in the classroom. Instead of hours making different worksheets, their attention can all be on using those resources to help the children they are teaching.

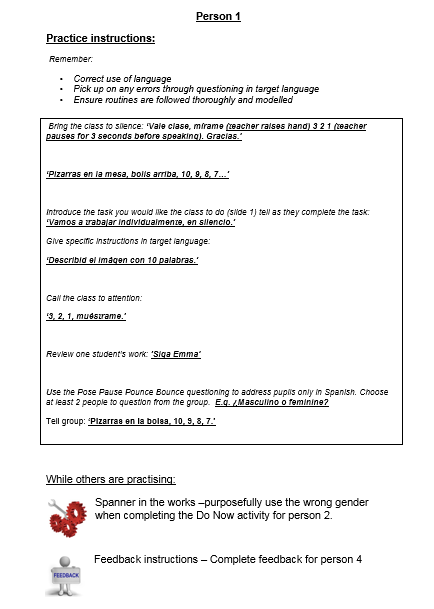

In my school, we have well-resourced lessons, and the benefit of these is enormous, letting me concentrate on this so-called final foot. Here are a couple of examples to illustrate it.

Brushing up on subject knowledge

In my post last week, I listed some sources for finding out about George Orwell and the context for Animal Farm. While I try to be efficient by listening to audiobooks and podcasts on the commute, time is finite. Rather than deskilling me and making me less likely to understand what I am teaching, having a good starting point for a lesson frees me up to pursue those aspects that increase my understanding and therefore improve my teaching.

Recently I taught The Charge of the Light Brigade, starting with a pre-planned lesson that already had retrieval practice questions in the Do Now, a model answer which was ready to unpick and even something simple: the poem copied and pasted on slides ready for me to annotate in class. This meant I had more time to think deeply about the poem, reread some notes and explore the context further. It took me to the original Times article which Tennyson would have read. You can see echoes in the language/tone of the poem in the article e.g. “ they flew into the smoke of the batteries”; “exhibition of the most brilliant valour, of the excess of courage, and of a daring”. I learnt much more about the Crimean War and understood that the Crimean War was the first where newspaper reports were ‘live’, albeit taking three weeks to arrive. From then I pursued the shift from event to news to poetry and the complications of stories told third hand, then the links to Ozymandias.

Crafting explanations

A good explanation can be the making of a lesson, but it can often be an afterthought – the planned lesson is seen as the endpoint. It’s all very well having a lesson ready and the notion that you’ll explain dramatic irony here or tell them what a subordinate clause is there. Yet there is an art to explaining these things – use the wrong words and they just don’t get it, or worse a misconception becomes ingrained (see other pitfalls in this great piece by Tom Boulter). A great explanation needs examples and non-examples, it needs analogy, it needs prior thought about the misconceptions that might arise. I think teachers should practise more, and a great explanation gets better with practice. These things can happen when teachers plan their own lessons, but when teachers plan all their lessons from scratch, this’ll happen less, or in the evening or weekend.

An example of a great explanation is this one from @positivteacha on iambic pentameter. You can see how deeply he has considered the sequencing of it and the examples he uses as exemplification. I used this to reconsider my own teaching of iambic pentameter when looking at Ozymandias. I used these lines to explain the metre: “Who said: ‘Two vast and trunkless legs of stone’” and “And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command” then asked them to see whether the following line was written in iambic pentameter: “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:” which led to some great moments of discussion. Then three questions to explore: How does the regular iambic pentameter combine with the irregular rhyme scheme to reinforce Shelley’s ideas?/ How does the iambic pentameter serve to diminish Ozymandias’ power?/ How does the regular iambic pentameter help to reinforce the idea of the everlasting and inevitable power of nature? Having ‘taught’ iambic pentameter for many years, this is the first time I gave it any real degree of thought. Again, this could happen without pre-planned lessons, but I’m not sure it would.

We have this norm in teaching, where it is taken as a given that teachers work long hours. Most professions wouldn’t entertain the thought – the job finishes when it does. We all want to do our best, but when this means that we have zero time for ourselves, our profession is unhealthy and our lives are unhappy.

Would I prefer to plan all my lessons from scratch? Probably. But the reality is that it takes time, and that time often comes in the evenings and weekends. Whether you are someone who disagrees with John Blake on this issue or not, I am firmly in the camp that teaching at present is an unsustainable profession, so I would welcome a range of high quality curriculum and lesson resources. It will make me a better teacher.

As Blake concludes the report:

No textbook or worksheet will ever substitute for a positive relationship between teacher and pupil but these “oven ready resources” can underpin those relationships by reducing teacher workload on activities which can be done effectively by external bodies. That then expands the time and energy available to teachers to deploy their professional skills where they will make the most difference, in “the final foot” between them and their pupils, in the classroom.