Designing a knowledge organiser is a difficult task and there are multiple decisions that affect their construction. They are complex but the idea behind this post is simple: Here is a Knowledge Organiser for Animal Farm and here’s how I made it.

Principles

I want the knowledge to be such that retrieval practice is easily facilitated, that information can be elaborated upon, and the material can be organised in multiple ways – all of which will support student revision and teacher pedagogy. I want things that are high utility, that are foundational for successful study of the text. I want to guarantee that 100% of students understand 100% of the material, but it is not the whole domain and will be supplemented by lots of explicit teaching. (I have written about the evidence behind all of this for the Chartered College if you want to read more.)

There are maybe some generalisable principles for English Literature as a whole, but I see this as an example of a Knowledge Organiser for Animal Farm, and not a template for all literature texts.

Content

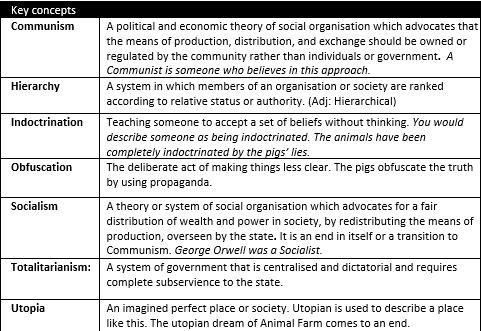

Key concepts: For this section I wanted to include some of the big ideas that pupils would need to consider. The biggest problem in this area was trying to define complex political ideas such as socialism while ensuring that it fitted in a small space. There are some compromises here, but none which wouldn’t be elaborated on constantly in class. And this is the point – if that sentence on a knowledge organiser was everything then it wouldn’t be enough. But when it is a reminder of a concept I have taught fully then that is a different matter. Another thing I did was add in adjectival forms of the words in sentence where appropriate so pupils could use in a range of contexts.

Key concepts: For this section I wanted to include some of the big ideas that pupils would need to consider. The biggest problem in this area was trying to define complex political ideas such as socialism while ensuring that it fitted in a small space. There are some compromises here, but none which wouldn’t be elaborated on constantly in class. And this is the point – if that sentence on a knowledge organiser was everything then it wouldn’t be enough. But when it is a reminder of a concept I have taught fully then that is a different matter. Another thing I did was add in adjectival forms of the words in sentence where appropriate so pupils could use in a range of contexts.

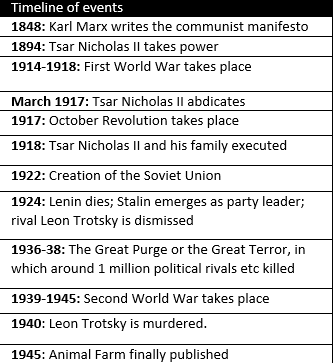

Timeline of events: I tried to help pupils build a chronology, most of which are paralleled by events in the text. I chose to use the present tense, perhaps giving more of a sense of history as living events. You can see how the section is very easily quizzable. One consideration was whether to continue the timeline beyond the publication of the text e.g. 1953: Stalin dies or 1949 Creation of the People’s Republic of China. In the end, I felt the publication of the text was an appropriate place to end the timeline, as anything after did not feed in to the ideas as intended. Also, space. I still think it is important to explore some of the later developments of communism for that wider conceptual understanding.

Timeline of events: I tried to help pupils build a chronology, most of which are paralleled by events in the text. I chose to use the present tense, perhaps giving more of a sense of history as living events. You can see how the section is very easily quizzable. One consideration was whether to continue the timeline beyond the publication of the text e.g. 1953: Stalin dies or 1949 Creation of the People’s Republic of China. In the end, I felt the publication of the text was an appropriate place to end the timeline, as anything after did not feed in to the ideas as intended. Also, space. I still think it is important to explore some of the later developments of communism for that wider conceptual understanding.

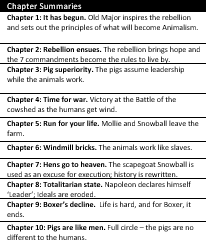

Chapter summaries: I considered whether this was necessary but Animal Farm is a book where chapters are sometimes indistinguishable from each other and events are more difficult to place. Things are the same; they just get a little worse each time. I decided to summarise with a simple statement that captured the essence of the chapter. I also create a rhyming cue to help them to remember it e.g. “Chapter 8: Totalitarian State.” In hindsight, this hasn’t proved as useful when teaching so it might go on a later revision.

Chapter summaries: I considered whether this was necessary but Animal Farm is a book where chapters are sometimes indistinguishable from each other and events are more difficult to place. Things are the same; they just get a little worse each time. I decided to summarise with a simple statement that captured the essence of the chapter. I also create a rhyming cue to help them to remember it e.g. “Chapter 8: Totalitarian State.” In hindsight, this hasn’t proved as useful when teaching so it might go on a later revision.

Character and themes: For this section, I created a clear line of argument about a character or theme. This was then supported by 2 key quotations. If it were just quotations, I don’t think it is as easy to memorise or contextualise so it would lead to rereading as studying and isolated quotations without context. The thesis was for me more effective than just a word as a cue e.g. Boxer – see here for more on developing a thesis. These quotations are possibly not always the best ones on reflection.

Character and themes: For this section, I created a clear line of argument about a character or theme. This was then supported by 2 key quotations. If it were just quotations, I don’t think it is as easy to memorise or contextualise so it would lead to rereading as studying and isolated quotations without context. The thesis was for me more effective than just a word as a cue e.g. Boxer – see here for more on developing a thesis. These quotations are possibly not always the best ones on reflection.

Ideas about Organisation and structure

In addition to definitions of these, I have tried to exemplify how we can write about them. This is to stop the listing of terminology without interesting analysis.

The Knowledge Organiser is one part of a well-designed curriculum. It should find itself fully embedded in the teaching and study that takes place. If it is integrated then it becomes highly useful interconnected knowledge which complements what is happening in class. Ideally, we should make them from scratch. Some aspects of this one come from my own understanding of what our pupils need. In making it from scratch, I deepened my understanding of the text.

I’m really interested in hearing feedback. What have I missed? How would you change it? What are you doing in your departments?