I couldn’t claim that we have all of the answers to CPD at Dixons Kings. However, I feel that we certainly ask the right questions. Here are 5 questions to ask that might help your CPD to be that little bit better.

Is everyone getting what they need?

Schools have priorities. Departments have priorities. Individuals have priorities and interests. We have biases and preferences, the things that we like to do and the things that we want to share. A balance has to be struck, of course, but if teachers leave a CPD session with nothing, then it simply isn’t worth their time.

At DKA, we split our teachers into two CPD sessions during the week and break these up further where necessary. While it is ultimately our decision on the overall content of the CPD program, it is informed by various factors to ensure that it is as personalised as possible. (On top of this, teachers get individual development through the coaching program.)

Are we sharing the right ideas?

When those who lead CPD say that something is the ‘right’ or ‘best’ way to do something, it is likely going to start appearing in classrooms, so we have to hold things up to scrutiny. In the past I was told that learning styles should be catered for, and I did it. I was told that teacher talk was bad, so I eliminated it. It’s all very well to blame others for this, but I have also given bad advice. I still shudder at the memory of the podcast I recorded on ‘showing progress’, or my suggestion in a blog that you could write feedback in code to ensure students engage with it…

Fashions and concepts of best practice change, so it is perhaps inevitable that some bad advice will be given. To avoid it, you always have to consider whether what you are sharing is received wisdom, a ridiculous fad, an inefficient drain on teachers’ time. Even when something makes sense, is it adding to workload? Last year, I ran CPD on my own, but this year I have benefitted from sharing the work with a colleague, Simon Gayle. He is brilliant at calling out any nonsense that I come up with, and vice versa. We hopefully filter out 99% of the possible nonsense, and any that we do share at least we agree on!

How do we ensure that it sticks?

If a focus for CPD is chosen, it needs to remain the focus for enough time to allow it to become just a part of practice. One session isn’t enough. You can’t just ‘do’ something or launch an idea, expect everyone to do it and then move on the next week. The individual sessions too have to be constructed in a way that people don’t just forget things as they walk out. This might involve tasks which ensure reflection or discussion, or even quizzes.

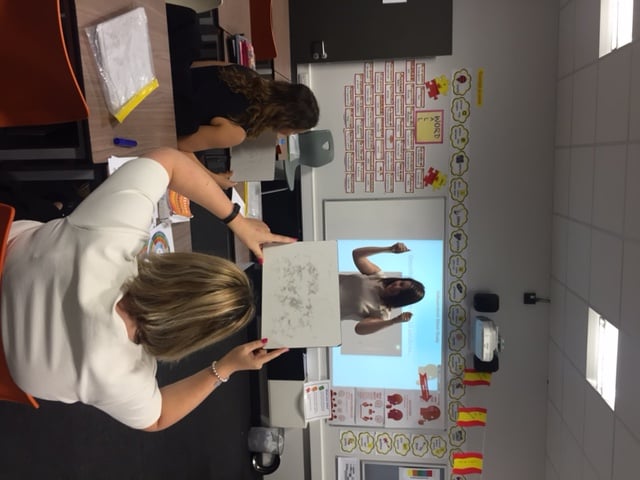

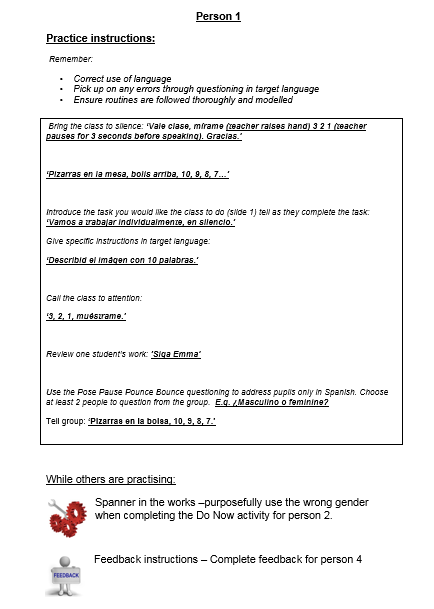

We organise our CPD around a half-termly focus. Last half-term was questioning, next half-term is revision & memory. We therefore plan a series of sessions which we hope develop a deep understanding not just of what teachers should do but why they do it. Another approach that we have is to practise anything that we can, have the theory one week and then follow it up with the practice.

How is it different for …?

It’s hard not to see teaching through your own lens. Teaching to me has always been English teaching and I used to believe that teaching was just a bunch of generic transferable skills. I think that there are definitely a range of things that all teachers can work on, but there are many things that are unique to their subject discipline. For example, you could share some modelling strategies with all staff, but the head of maths shouldn’t model how to do a backflip. You have other considerations like heads of year who may suddenly have all of their free time taken to deal with an incident, teachers who don’t have their own classroom, non subject specialists, split classes- and the list could go on. You can’t put on a session for cat-lovers born in February, but you can at least consider the impact of what you do on as many teachers as possible.

A couple of weeks ago, we looked at feedback strategies and we split the session into three. One priority was ensuring that there was a session focussing on feedback in practical subjects (another session was a walkthrough of using mail-merge marking, with the other on timesaving marking strategies). We are also looking to develop our CPD model further to allow teams even more time for subject pedagogy to be developed.

How will we know that it works?

This is the trickiest question to answer. You can evidence compliance quite easily, but this is not the same as something working. This is the area we have tinkered with quite a lot this year and continue to try to get right, so it’s the question on this list that I have the least comprehensive answer for.

One useful start is our half-termly anonymous survey. It has various questions that help us to understand what is going on in classrooms and how people feel about the quality of our CPD. Two questions we always ask are: ‘What are giving you that you don’t need?’ and ‘What do you need that we are not giving you?’ The feedback sessions came out of requests from this survey, as do many of the sessions next half-term. We can compare responses from each half term to the next, showing where improvements have been made and identifying where we might focus next. We can compile data from other sources too, e.g. book scrutinies and learning walks, but it is harder to tie these to specific CPD sessions.

Like I say, we don’t have all of the answers, but I’m happy that we are asking these questions. If you have any other questions worth asking, or indeed some of the answers, feel free to comment.